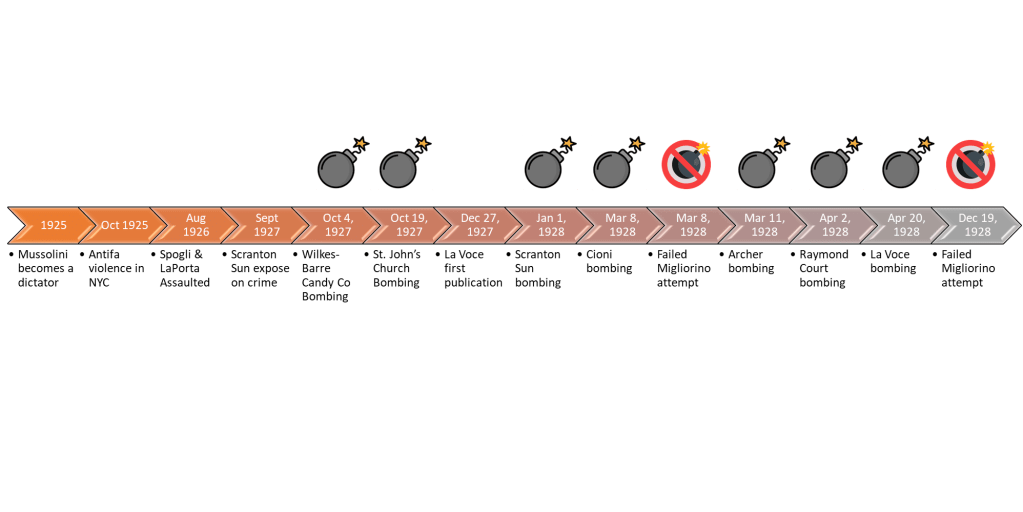

Today, Antifa is known as a “movement” of far-left-wing antagonists. The autonomous and loosely organized anti-fascist group seemingly reemerged after Donald Trump was elected in 2016. Since then, they have been active in violent and non-violent demonstrations nationwide. The height of their activities came during the summer of 2020 when cities around the country burned in response to George Floyd’s death.

But did you know that the anti-fascist movement has been around for more than a hundred years – and was active in Scranton during the 1920s?

Rise of Fascism

In 1922, Benito Mussolini took over Italy’s leadership after tens of thousands of his armed supporters marched on Rome. They demanded that King Vittorio Emmanuel III name Mussolini the Prime Minister. In response, the King dissolved the current form of government and asked Mussolini to step in and create a new one.

March on Rome – 1922

Associated Press Photo

Three years into his reign, in 1925, Mussolini essentially changed the rules. He declared that the prime minister (himself) was now the head of government and did not have to go through any legislative process to enact new laws. He added that he could only be removed by the King.

Mussolini became known as the first fascist leader, pushing his agenda to strengthen Italy’s national identity by restoring its pride and economic power after the First World War. In and of itself, those aren’t bad goals, but how he went about it caused his fall from grace. His economic policies and military blunders, like aligning with Hitler and his position against Jews, revealed his true character.

During his time in power, Mussolini became an authoritarian dictator, suppressing his opponents by having them arrested. He controlled the media by financially rewarding friendly outlets with subsidies. At the same time, he drastically increased the size of government by hiring his cronies – who would support him endlessly.

Scranton’s Involvement

So, what does this have to do with Scranton? Well, in 1926, Scranton was the third-largest city in Pennsylvania, with over 143,000 residents. It was also the 38th-largest city in the country at that time. For perspective, today, Kansas City is the 38th-largest city in the US, with over 500,000 people. And Scranton doesn’t crack the Top 350 in population.

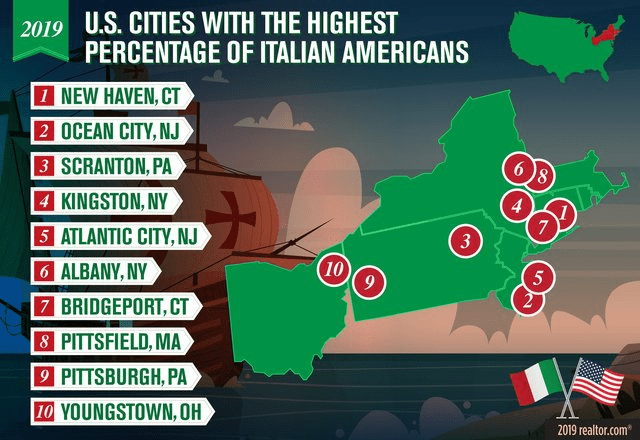

At the time, Scranton was also home to tens of thousands of Italian immigrants. Large pockets of Italians could be found around the city in places like Bulls Head, West Scranton, and South Scranton. Elsewhere in Lackawanna County, places like Jessup, Carbondale, Dunmore, Pittston, and Old Forge also had large populations of Italians. Even as late as 2019, Scranton was listed as #3 in the percentage of Italian-Americans – based on a survey from Realtor.com.

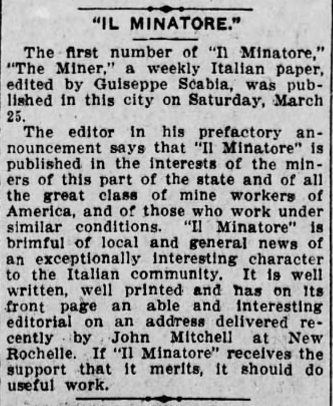

In fact, there were so many Italians in Lackawanna County that at least two Italian-language newspapers were operating in Scranton. Il Minatore, aka, “The Miner,” started publication in March 1911. It was later joined by La Voce Italiana, aka, “The Italian Voice,” which started in December 1927. More on that later.

Violence Erupts

During Mussolini’s reign, fascism was a hot topic around the globe, including the Italians in Scranton. The division in ideology spawned the creation of two opposing national organizations.

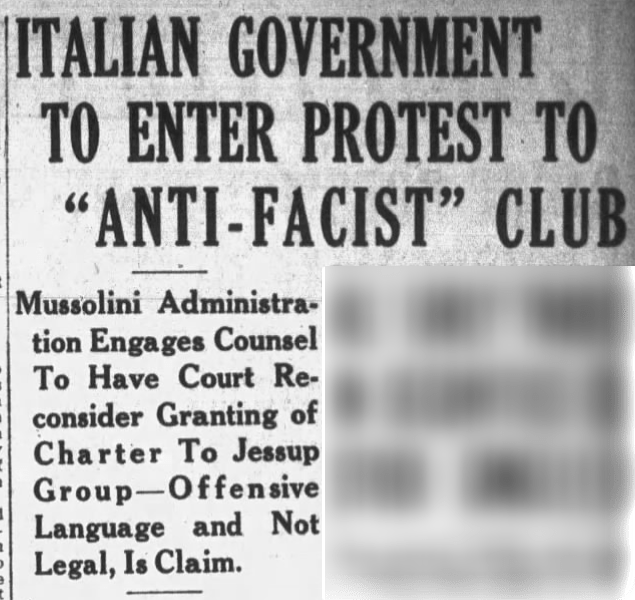

By the mid-1920s, the Italian-American Anti-Fascisti Association and the Fascisti League of North America were born and both had chapters nationwide – including a Jessup chapter of the Anti-Fascist Association.

August 26, 1927

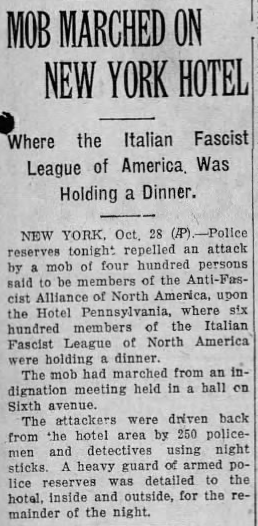

Tensions between the two sides escalated over the years. Anti-fascist members were protesting their counterparts around the country – like at this dinner in New York City when an angry mob of anti-fascists disrupted an Italian Fascist League dinner party.

October 29, 1925

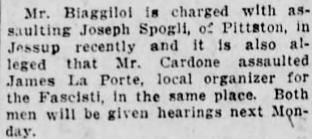

The violence reached Lackawanna County by August 1926. Luigi Biaggioli, Enrico Monacelli, and Benvenuto “Lullo” Cardone, all members of the Anti-Fascist Party were accused of assaulting members of the rival Fascist party.

In November 1926, the cases were heard in court. The Mussolini-backing Fascists scored victories in all cases with fines for Biaggioli and Cardone while Monacelli was sentenced to prison.

November 23, 1926

Regardless, DA Harold Scraggs scolded both sides for their actions, saying, “Both (parties) should be driven out of the county and the country.” Adding “If it was moral turpitude, they could be deported.”

Vito Bianco

During the November trials, Vito Bianco, a native of Guardia Lombardi, Campania, Italy, was in attendance in support of Spogli and others who were attacked by anti-fascists.

Times Leader

May 30, 1927

Bianco was a prominent man in the business community. He was a banker and a candy maker in Pittston. He was also a leader in the Sons of Italy and Fascist League of North America organizations, having been awarded commendations by Pope Pius XII and Italian King, Vittorio Emmanuel. He was also reported to be a close personal friend of Mussolini.

April 19, 1926

After the hearing, Bianco was quoted as saying, “We do not have any cases in court. None of our members (Fascist League of North America) are charged with breaking the law. The aim of our organization here is to teach Italians to obey the laws of the United States and we are trying to make better citizens of them. The preamble to the constitution of the Fascist League of North America sets forth one of the aims of the league – to love, serve, obey, and exalt the United States, and to teach obedience to and respect for its constitution and laws.”

A month later, in December 1926, Bianco testified in front of a parole judge to have Monacelli, the anti-fascist, released from prison. A move that would seem to signal de-escalation and support for his fellow countrymen.

Violence Escalates

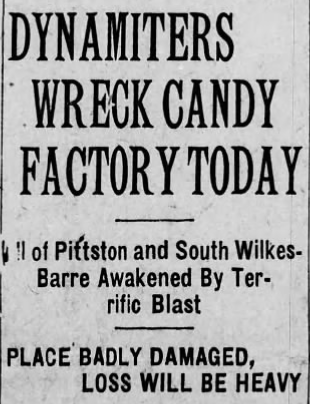

But the violence continued – and escalated. In the early morning of October 4, 1927, an explosion destroyed the Vito Bianco’s Wilkes-Barre Candy Maid Company in Pittston. Vito owned the business with his brother Joseph.

October 4, 1927

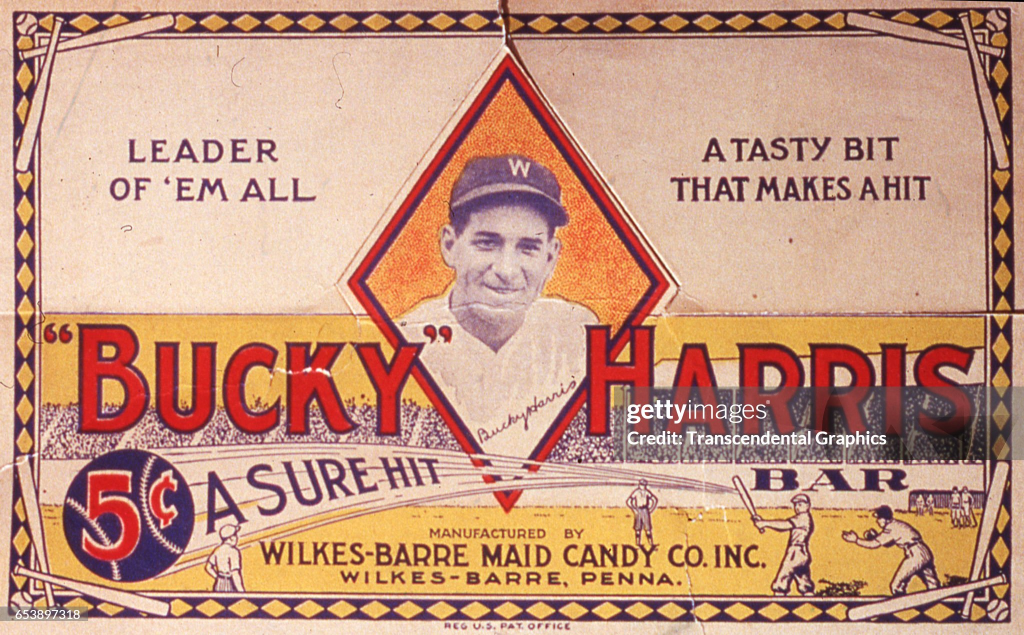

Side note: Around the same time the Babe Ruth candy bar was introduced, Bianco’s Wilkes-Barre Maid Candy Company introduced its signature candy bar. The Bucky Harris was named in honor of the Pittston baseball legend, Stanley Raymond “Bucky” Harris.

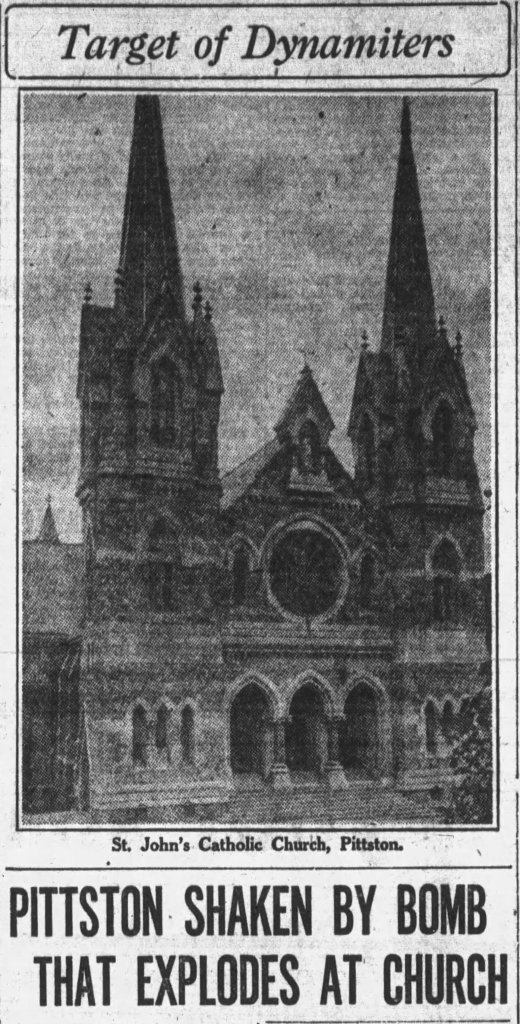

St. John’s Catholic Church

The candy factory blast was followed by yet another bombing just two weeks later. This time at St. John’s Catholic Church in Pittston. It was reportedly in response to the Mayor offering a reward for information leading to the arrest of those responsible for bombing the Bianco business. This marked the fourth attack in a matter of weeks within Pittston – and several others in Lackawanna County.

October 19, 1927

Scranton Sun

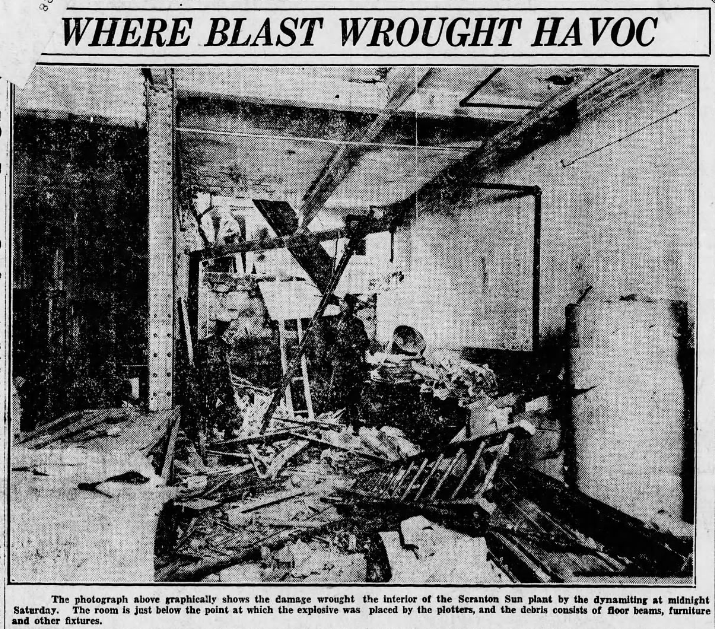

A couple of months later, as the city was ringing in the New Year on January 1, 1928, a blast ripped through the plant of The Scranton Sun The local newspaper was located at 314-316 Adams Ave. Fortunately, no one was severely injured.

January 2, 1928

January 2, 1928

The relatively new Sun opened its doors in September 1926 and professed to deliver local news with a “well-balanced staff of editors, news writers, artists, and photographers.” It’s not clear if they backed, opposed, or were indifferent to Mussolini.

August 26, 1926

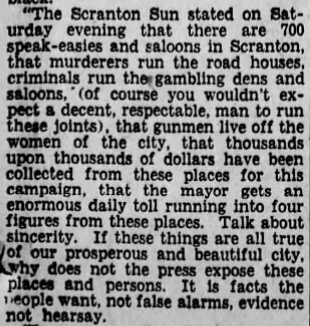

A year after opening, in September 1927, they printed an “expose” on crime in Lackawanna and Luzerne counties. The paper claimed that bootlegging, gambling, and white slavery (prostitution) were ubiquitous throughout the two counties. They claimed that over 700 speakeasies and saloons were operating in Scranton at that time.

The Sun editorial staff accused an organized criminal gang from Pittston of being responsible for the businesses and related corruption. It was generally believed that this accusation led to the New Year’s Eve bombing.

September 19, 1927

A Pittston man was a suspect in the blast and was questioned by authorities. He was later released and no one was ever held responsible for the blast.

Related or Coincidence?

While investigators tracked down other leads for the Sun bombing, the violence didn’t stop. Several other attacks occurred throughout the city in the early months of 1928. The homes of Pasquale Cioni, 206 Chestnut Ave (Now St. Frances Cabrini), and Charles Migliorino, 918 Cedar Ave were both targeted on the same evening in March 1928.

March 8, 1928

Migliorino was lucky and averted disaster. It was believed that the wind had blown out the fuse on the package that was left at his home.

March 8, 1928

Days later, Vincenzo Arciere (aka James Archer), 1417 Diamond Ave was targeted. Arciere was known to illegally serve alcohol out of his grocery store.

March 12, 1928

And finally, a “disorderly house” at 228 Raymond Court was blasted in the early morning hours of April 2, 1928. Police identified four suspects. Vincenzo Macorini, Scranton; Anthony Mastola, Buffalo; Mary Russell, Niargara Falls; and Victoria Smalls, Tamaqua all were questioned and released due to lack of evidence. They were known as “denizens of the underworld” according to the Scranton Times.

April 2, 1928

Investigators tried to connect the bombings, but could not tie any of them together. At this point, dynamite blasts were almost common throughout the city with at least four blasts and one failed attempt in just over four months.

Anti-Fascist or Newspaper Quarrel?

Just before midnight on April 20, 1928, another explosion rocked the building that housed La Voce Italiana, the new Fascist newspaper in town. The blast was so strong that it affected several other nearby buildings. This was now reported as the fifth dynamiting in the city since the beginning of the year.

April 21, 1928

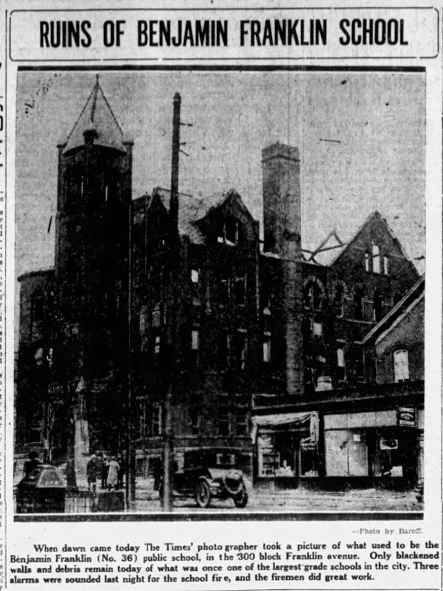

Officials were already busy fighting a massive fire at the Benjamin Franklin School just down the street and were quick to respond.

April 21, 1928

They rushed to the scene and found debris scattered as far away as Kaplan’s Furniture store on Lackawanna Ave. Windows on all the buildings in the immediate area were blown out, including all those of the rival newspaper, Il Minatore, just across Center St.

Kaplan’s was said to have lost about a hundred windows, including four massive showroom windows fronting Lackawanna Avenue. And Bittenbenders, at 126 Franklin, lost a dozen windows. Center Street was deemed impassable due to all of the brick and debris from the explosion.

April 21, 1928

Initially, fire officials weren’t sure if the school fire and the newspaper blast were related. It was later determined to be a tragic coincidence – along with another fire that broke out even later in the evening that eventually killed a grandmother and grandson in North Scranton.

Emergency crews sifted through the smoke and debris. They found several people in shock, including La Voce employees and tenants of the rooming house above. Six people suffered minor injuries, but fortunately, no one was killed.

Printing press buried under the debris

President Ross Cammarata, editor Filippo Bocchini, and press operator Edward Mariotti were in the front office when the blast occurred. They were thrown to the floor but escaped any serious injuries. Luckily, William Bedford, a press operator, left twenty minutes before the blast.

The injured included two tenants from the rooming house on the second and third floors of the building and La Voce’s janitor.

It was estimated that the blast caused over$20,000 to La Voce and $150,000 in damage in total (about $2.7M today) to the buildings and businesses in the area.

La Voce Italiana

La Voce Italiana, translated to The Italian Voice, started publishing just months after Bianco’s candy business was bombed. It became the second Italian newspaper in Scranton, and the first to support Mussolini. It was printed at the rear of 116 Franklin Ave, at the corner of Center Street, and was distributed every Saturday starting December 22, 1927.

When the paper first started, the editor was Dominick Stivale. Stivale operated his Italian Imports store in the same building.

October 12, 1927

November 2, 1927

The President of La Voce was Rosario Cammarata of Throop and Vito Bianco (the same Vito Bianco) served as the treasurer and secretary.

Around March 1928, the paper had undergone a leadership change. Filippo Bocchino, a man brought in from Philadelphia, was the new editor and Stivale would take over as the advertising manager and assistant secretary.

Il Minatore

Il Minatore, translated to “The Miner,” was published across Center St from La Voce. Its origins date back to March 1911. Umberto Molinari, an Italian immigrant to the US from the Northern Italian comune of Cremona in Lombardy, joined the newspaper early on as its editor. He would later purchase the paper. The newspaper was against Mussolini and supported the Italian-American Anti-Fascist Association.

March 30, 1911

February 27, 1927

Coincidentally, Umberto’s brother, Alberico Molinari published the Socialist Newspaper, Ascesa, in Scranton from 1905-1911. He too was a known anti-fascist, getting arrested in Chicago as part of a labor strike.

Alberico would return to Italy and was banished to the Island of Sardinia for three years for his actions as an anti-fascist.

September 28, 1948

Investigation

Some immediately thought that it was a dispute between the two Italian newspapers. Of course, officials of Il Minatore strongly denied any accusations. And La Voce officials said that nothing had been published that could justify this level of violence.

April 21, 1928

Others felt it was another targeted attempt at Vito Bianco – since his candy shop was hit just months prior. And, still others believed that it was Antifa striking against the fascist newspaper.

Mariotti and Bocchini told investigators that they saw a man peering in the windows just before the blast. They dismissed it thinking it was just someone interested in seeing how the printing press worked – as it was a common occurrence.

Investigators believed an open cellar window provided access to the bomber, but could not find any other clues or suspects.

Unsolved Mystery

The La Voce blast was the final one in a string of bombings in Scranton and Pittston. Thankfully, no one died in any of the blasts, however, Charles Migliorino did die of a heart attack just months after the attempt to blow up his home. Perhaps the stress of being targeted was too much.

July 27, 1928

Except for the Newspaper bombings, most were executed while the owners or occupants were not home – seemingly to send a message.

The best I can tell, no one was ever held responsible for any of the bombings. Investigators claimed that the targeted victims knew more than they shared. Rumors swirled. Was it Antifa vs Fascists? Was it the work of the Black Hand intending to intimidate their targets? Was it a newspaper feud?

April 23, 1928

Personally, I believe it was a combination. And dynamiting was the normal accepted practice of attacking and intimidating at that time.

The Black Hand was known for extorting money from businesses or otherwise wealthy Italians. Cioni was an undertaker, Archer a grocer/tavern, and Migliorino was a huckster. It would seem to fit the MO of the Black Hand – either pay for protection or become a target. The Black Hand preferred to keep their targets alive – so they could continue to pay.

I believe the Sun bombing was the work of the Pittston gang which ran or was heavily involved in, most of the criminal gangs in the area. They probably wanted retribution for being called out by the Sun’s expose – and they didn’t care if people were injured in the attack.

The La Voce bombing was likely the work of Antifa and/or Il Minatore. The rival newspaper despised their views and was probably even more irked when they moved in next door and started their business of spewing pro-Mussolini rhetoric. Again, they didn’t care if people were injured.

The final attempted bombing was in December 1928. The Migliorino home was once again targeted – even after Charles passed away. His widow claimed she knew of no one who would want to harm her or her family. I will say, this one is perplexing. Could there be more to the story?

December 19, 1928

After that, the attacks were seemingly called off and the city was quiet for a year – until a new round started in January 1930. More on that in a follow-up post.

Leave a comment