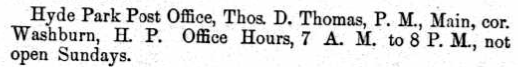

On the evening of Wednesday, October 20, 1875, Archibald Anderson of Providence was told he had a letter waiting for him at the post office in Hyde Park, located at the corner of Washburn and Main.

After dinner, he left his boarding home and made his way to pick up the letter. Once he did, he was struck with horrible news. His brother in Glasgow, Scotland, had passed away. The brother had recently visited Scranton and returned to his homeland.

Grief-stricken, he walked back to Providence, totally unaware that his night would get even worse.

Nervous Encounter

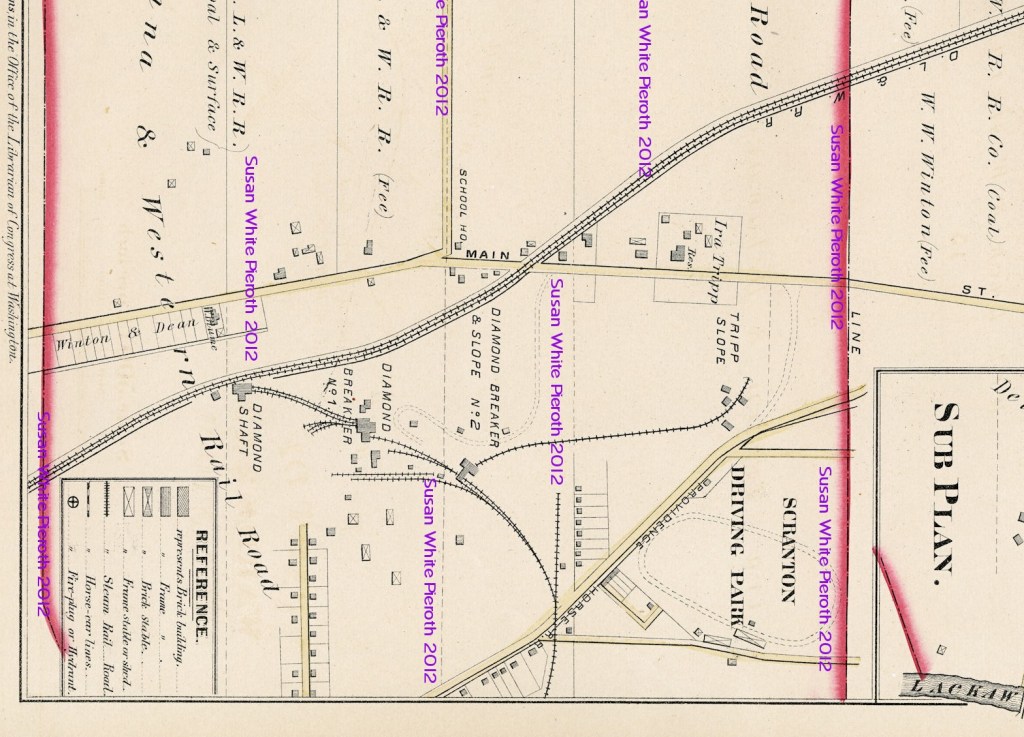

His return trip took him back up Main Avenue towards North Scranton. When he got to the Griffin Cemetery, he crossed over a wide ravine that ran between the Diamond Breaker and Tripp’s Slope. Today, the area is known as Ravine St.

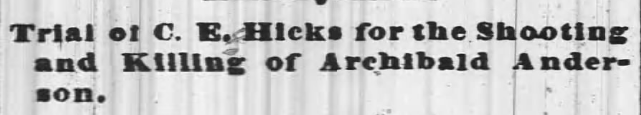

Courtesy: Susan White Pieroth

Just as he did, a young man appeared seemingly from nowhere. Without hesitation or words, the stranger fired a single shot directly into the stomach of Archibald.

The stunned victim fell to the ground. He moaned and yelled that he had been shot. The assassin told him to be quiet, or he would shoot again. Leaving his victim behind, the gunman ran from the scene.

First on Scene

Moments earlier, Dennis Shallue exited the horse-drawn streetcar that followed Providence Road toward Bull’s Head. He got off around Center Ave, now Philo St. At the time, it was the site of the city courthouse.

From there, he began walking toward his home along Main Avenue, south of the courthouse. Just as he started walking, he heard someone quickly approaching from behind, so he waited for the man to pass.

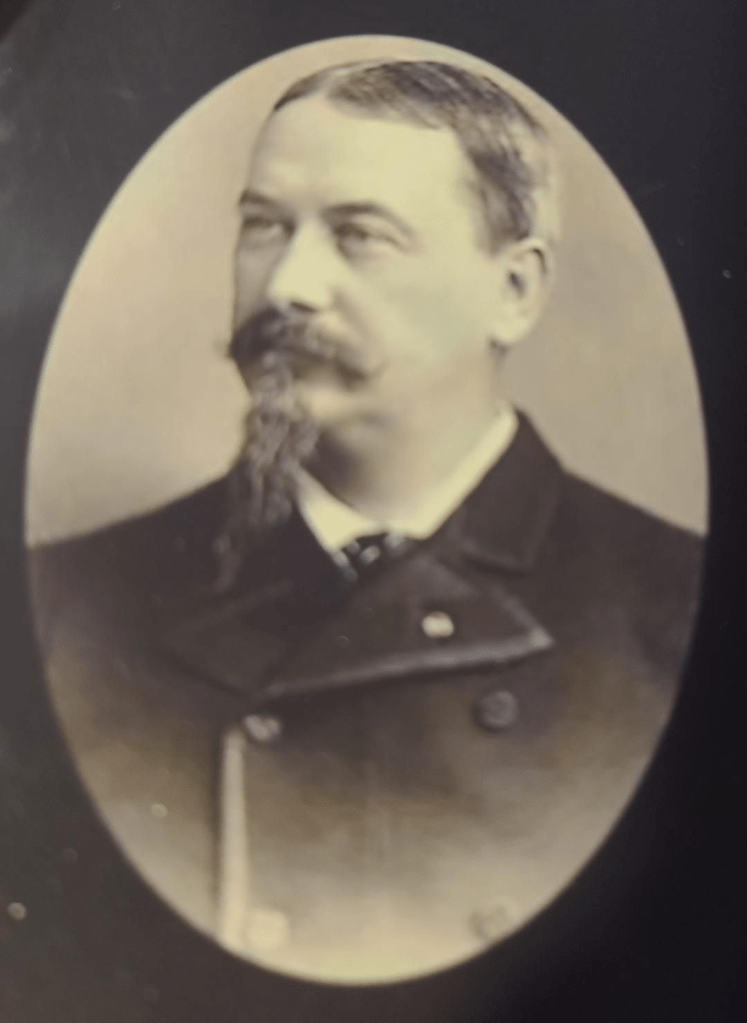

Courtesy: George Gula

The two men acknowledged each other, then walked steps apart. A short distance later, the men bid farewell as Dennis turned toward his home, and the other man continued along, travelling south on Main Avenue.

Courtesy: Lackawanna PAGenWeb

Dennis said he made it only about 30 steps before he heard a shot. He turned around and ran toward the screams.

As he did, Archibald was running towards him, crying out, “Murder!” and that he had been shot.

More Help

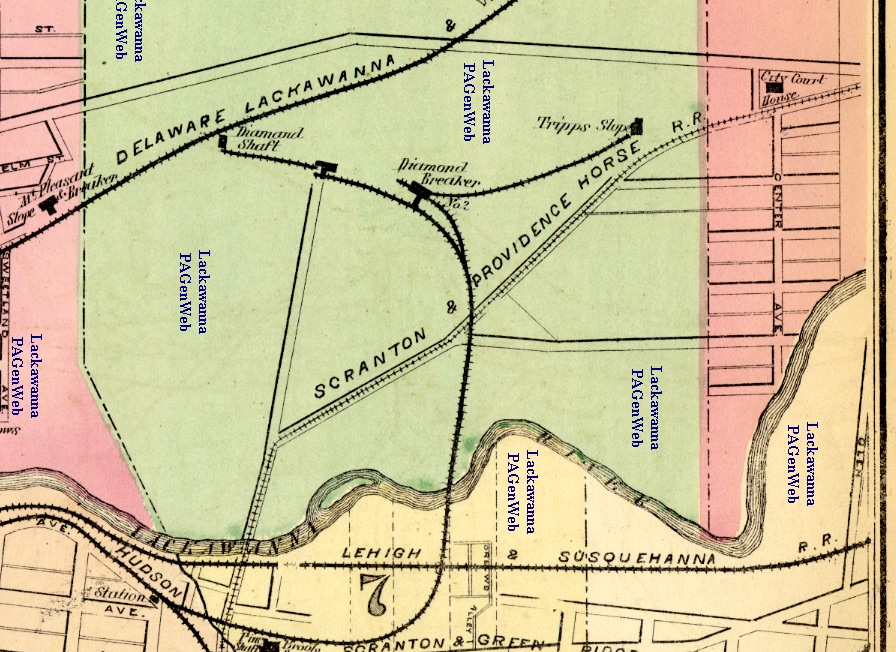

John Hawks, a mason who lived on Main Avenue, heard the gunshot and asked his wife to open the door. As soon as she did, she saw Archibald was outside. The wounded man said to her, “Oh!, Mrs. Hawks. I’m shot.” Just then, Mr. Hawks came to the door. He jumped in and helped Archibald make it home, about 250 feet away.

As a side note, John Hawks was born in Ireland in 1832. He came to the United States in 1840 with his parents, and they settled in what was then Slocum Hollow. John was credited with designing the first American flag that flew in the village. He carried the same flag as he led the first St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Scranton in 1855. Hawks was the marshal for every St. Patrick’s Day parade from 1855 through 1876.

March 17, 1922

Anderson Speaks

On their way to his home, Archibald told Mr. Hawks that he had just received the letter of his brother’s passing, and that now he, too, was going to die. He told him that the man shot him for no apparent reason. He said he was told that if he kept making noise, he would shoot him again.

Anderson was living at the home of Cyrus and Catherine Wademan at the time. When they arrived, Hawks instructed one of the young Wademan boys to go get a doctor.

Mrs. Wademan said she had heard the shots coming from the direction of Hyde Park. She made Archibald comfortable, and Hawk set out for Scranton to get Dr. Leet, whose office was on Lackawanna Avenue.

Anderson described the shooter as a young man in a white hat who was carrying a bundle of papers under his arm. He wore a dark coat and was slightly taller than Archibald.

Prognosis

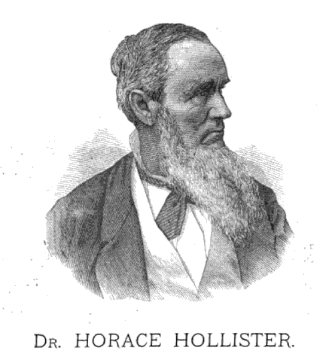

Dr. Horace Hollister had his office on Main Avenue in Providence. He arrived within 10 minutes and found Archibald lying in bed with a bullet wound about three inches from his navel, towards the right side of his body. After his initial assessment, the doctor provided some morphine to quell the pain.

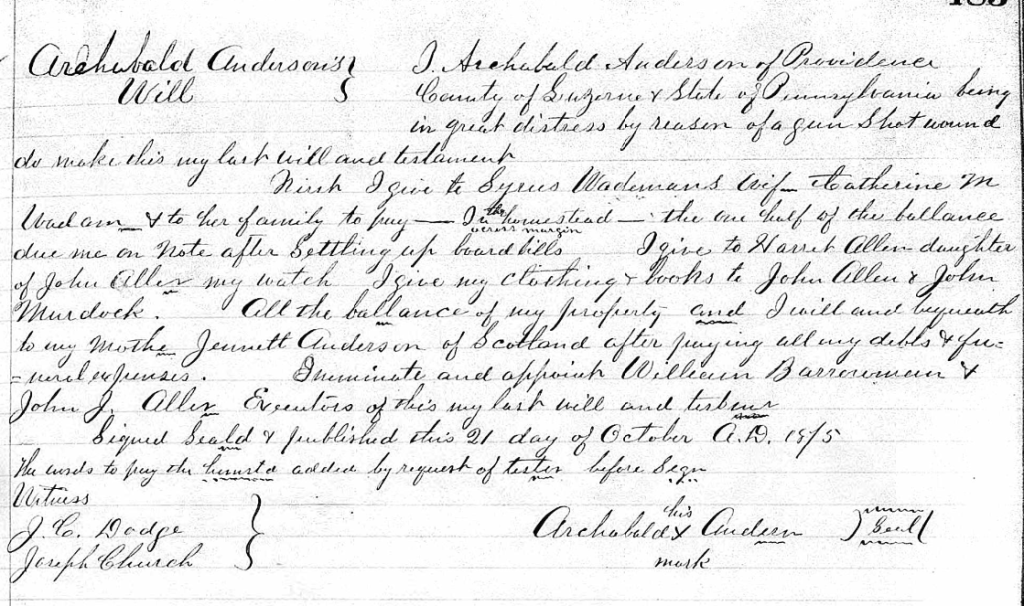

The doctor told Anderson that his prognosis was not good. He suggested that if he had any business, he needed to address it quickly.

November 25, 1875

Ante-Mortem

Later that evening, Archibald met with Alderman Leach to document his side of the attack.

Anderson said that he knew the man by sight, but not by name. He said, “We met on the road, on the main road near the graveyard (Griffin Cemetery). As he passed me, he stepped back about three feet and shot me. He said nothing before he shot; (he) said something after he shot, but I could not say what he said. I made no violent movement towards him.” He continued, “He had a paper bundle under his arm. I think he had a white hat on, and he was well-dressed. I was on my way home from Hyde Park when we met.”

Wound Proves Fatal

The next day, Dr. Hollister checked back in with Archibald several times. Each visit, he found his patient in extreme pain and growing weaker. And each time, he administered more morphine, allowing Archibald to pass away as peacefully as possible.

Archibald died around 7:00 p.m. on Thursday, October 21, 1875. He was laid to rest in the Wyoming Cemetery in Wyoming, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

Coincidentally, when Dr. Hollister passed away in 1893, he was recognized as the leading authority on Lackawanna Valley history. He had a collection of Native American relics and other evidence of their time in the region.

Courtesy: History of Luzerne, Lackawanna, and Wyoming Counties, Pa

Archibald Anderson

Archibald Anderson had been described as an excellent citizen. He was a single man who built quite a financial fortune for himself before his death. He was described as a sober, hard-working man. Industrious and peaceful.

November 12, 1875

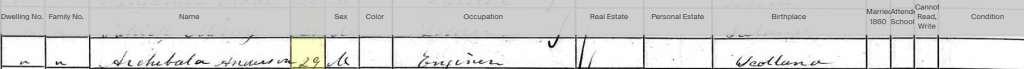

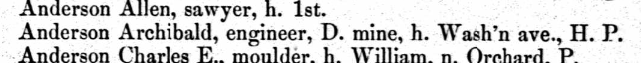

In 1860, Archibald was boarding with a coal miner and his family in Plymouth, PA. His occupation was listed as an engineer.

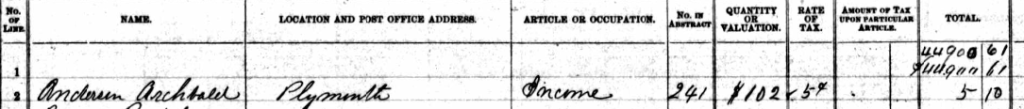

In 1866, he was still in Plymouth and assessed his income tax. He owed $5.10 based on his annual income of $102. That equates to about $3,900 today. Clearly, he wasn’t wealthy just yet.

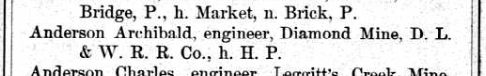

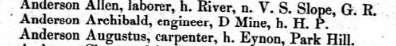

By 1870, he moved to Scranton and was working as an engineer in the nearby Diamond Slope.

And finally, by 1875, he was listed as living on Washington Avenue in Hyde Park. Washington became Lafayette Street when they renamed many streets in 1883. It’s not clear when he moved in with Cyrus Wademan, but it was likely within a year.

It was reported that Archibald made at least three trips back to his native Scotland during his time in the United States. That’s no small feat during the mid-1800s.

Just before he died, encouraged by Dr. Hollister, Anderson created his last will and testament. He left his watch to Harriet Allen and his clothes and books to John Allen (Harriett’s father) and John Murdoch. After paying off his debts, he left the balance to his mother. It was estimated that he had accumulated property of between $25,000 and $30,000. That equates to about $730,000 and $870,000 today!

He also instructed his friends to not divulge the manner of his death to his mother. He was concerned that, being 80 years old, she would not be able to handle the death of another son, especially in this violent manner.

The Suspect

It didn’t take long to identify the suspect. Because he initially survived the shooting, Archibald was able to provide a description of his attacker before he passed. This information allowed Dennis Shallue to confirm it was the man who had walked with him from the streetcar.

The morning after he shooting, Shallue went to visit another Park Place resident, Joseph Church. Church was a well-known resident of Providence. He owned a hotel that was located at the corner of Main Avenue and Church Street (now Wood Street). Shallue told Church that there was a shooting the night before and that he believed that he had walked with the suspect from the railway. He said it was late, and the man was walking towards the Tripp residence along Main Avenue.

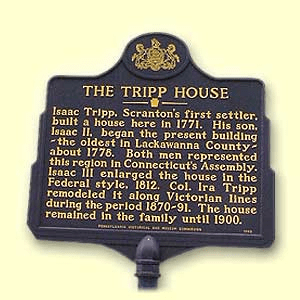

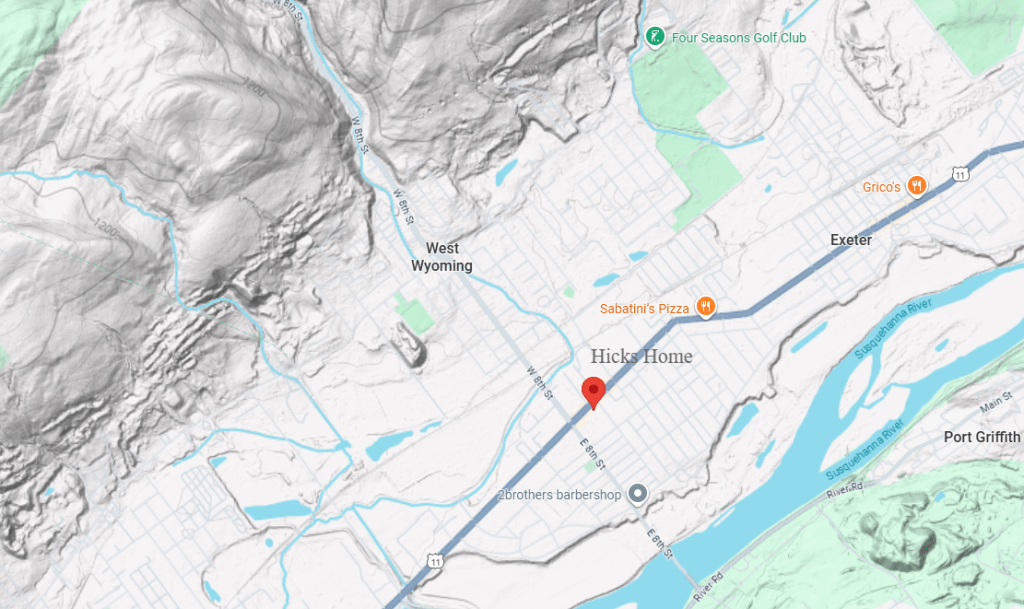

The two men went to the Tripp’s Slope mine and described the suspect. There, the men told them that it sounded like E.C. Hicks and that they could find him at Ira Tripp’s home, just up the hill.

October 30, 1875

The men made their way to the Tripp home. When the barn came into view, they saw two men quickly mounting horses. One man resembled Hicks; the other was later identified as Mr. Brown.

Courtesy: tripphouse.com

They asked Hicks to identify himself. The young man remained silent as he and Mr. Brown tried to bypass the two visitors. Shallue and Church blocked their way and said they couldn’t go anywhere because they believed that Hicks had murdered someone last night.

Courtesy: tripphouse.com

Mr. Brown said that he and Hicks were on their way to Providence, where Hicks was going to give himself up to Squire Ebenezer Leach.

Hicks added that Archibald had come upon him suddenly. It was dark. He had heard of a recent shooting in Scranton and was on alert. When Archibald appeared, he thought he was going to be attacked, and he “let flicker.”

The men made sure Hicks went to Providence to turn himself in.

E.C. Hicks

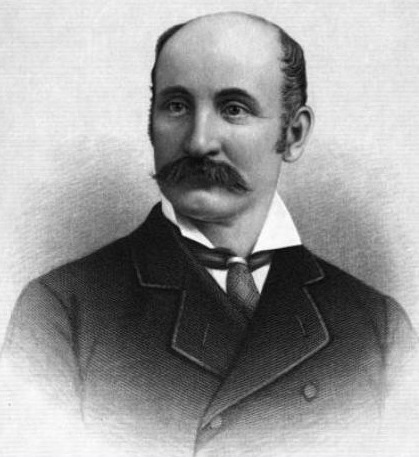

Edward Carroll Hicks was the son of Major James and Sarah Hicks. He worked for Ira Tripp at the Tripp’s Slope. But he wasn’t just a miner. He was a weighmaster, making sure each worker was paid appropriately for their load. He also acted as a “docking boss,” docking the pay of the men if their coal was not clean.

Major Hicks was prominent in Luzerne County, earning his title during the Civil War. He was a well-known farmer and breeder of Hambletonian horses. He was also a good friend of Ira Tripp.

The Tripp family is recognized as the first settlers in Scranton. They were one of the most respected and successful families in town. The Hicks family, by association, was also well-respected.

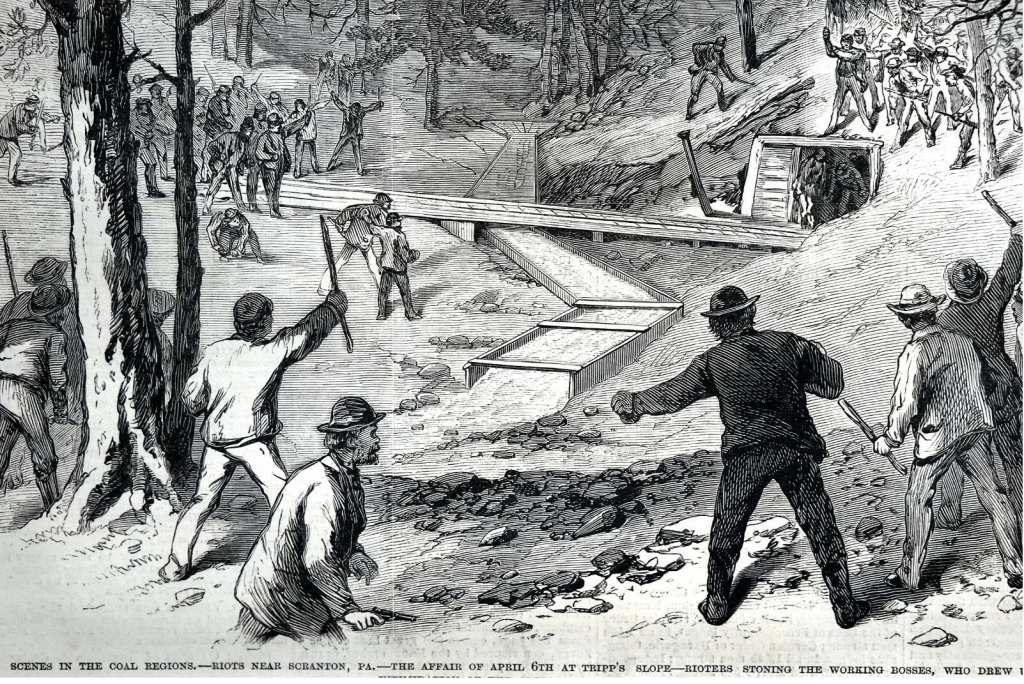

And while the Tripp family was wealthy, they weren’t without controversy. Just four years prior, the workers of Tripp’s Slope had rioted due to poor working conditions and low wages.

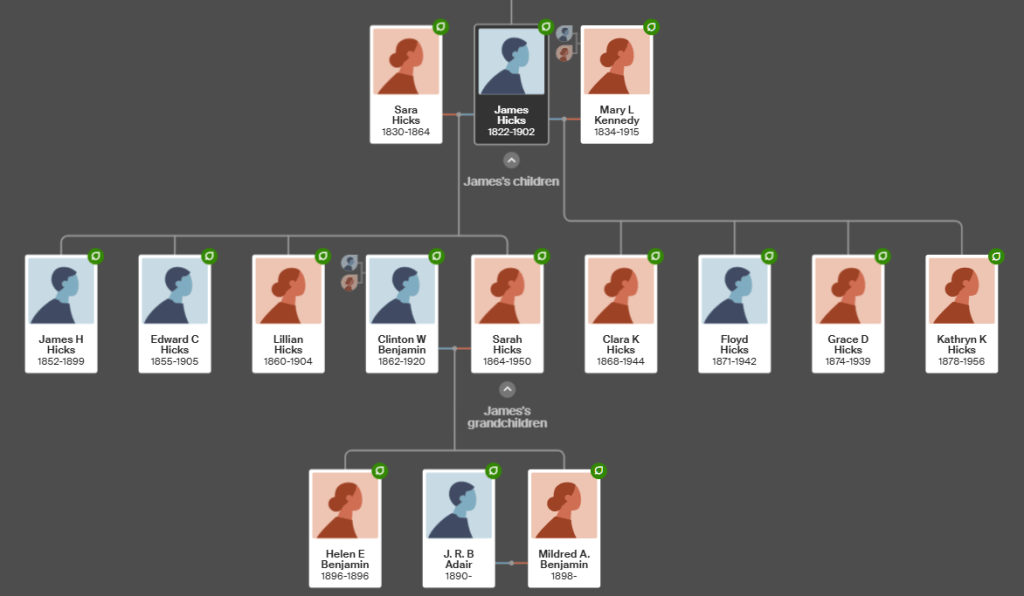

Hicks Family

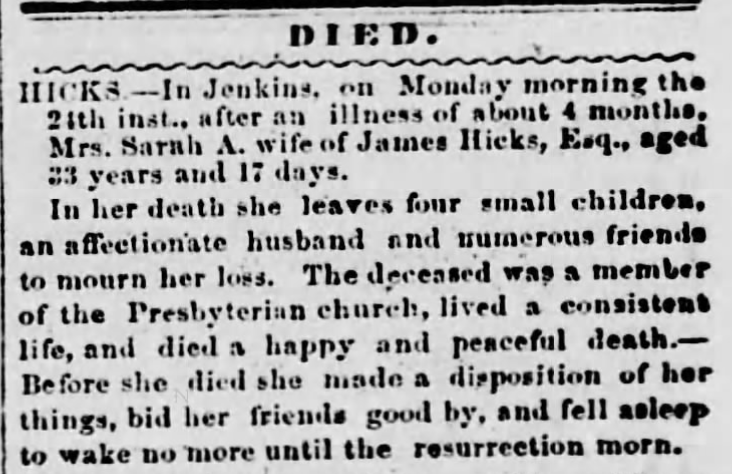

James had four children, including Edward, with his first wife. Tragically, Edward’s mother passed away in 1863, when Edward was only eight years old.

August 27, 1863

James remarried Mary Kennedy in 1869 and added four more children to his family.

Mary was a teacher, and the Hicks children were well-educated. James Jr graduated from Lafayette College and became an engineer, working as far away as Colorado. Three of the four girls, Lillian, Clara, Grace, and Kathryn, were all college-educated and followed in their mother’s footsteps as teachers.

Immediate Aftermath

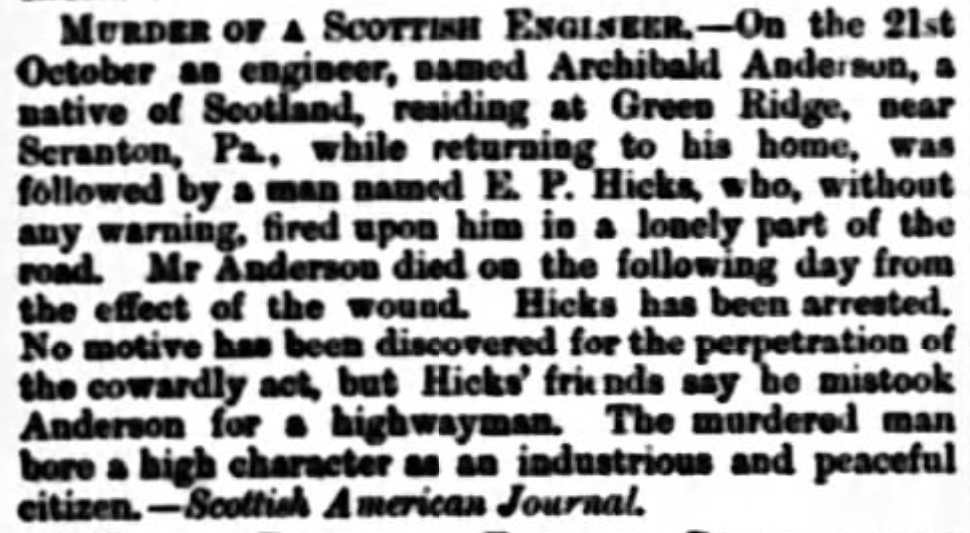

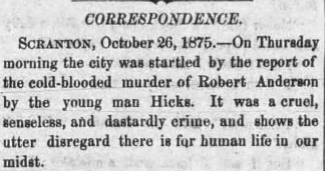

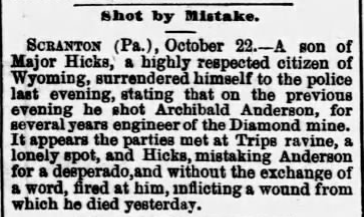

News of the attack stretched across North America, reaching as far as San Francisco and up into Ontario, Canada.

October 23, 1875

Oct 22, 1875

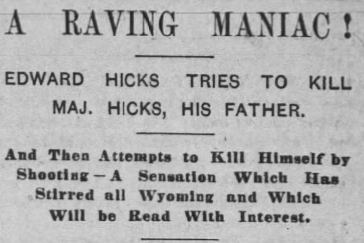

The Scranton Morning Republican demanded justice be served. While they stopped short of calling the murder premeditated, they let it be known that Hicks acted out of cowardice and irrational fear. They added, “We believe that the public safety demands that severe punishment be visited upon one who, walking along a public highway, deliberately fires upon the first person he meets.”

They continued, “It is no excuse for him that he was ‘frightened,’ that he thought himself ‘in danger,’ that he did not know what he was doing.” The public bashing continued with, “He doubtless would have killed his own father, or anyone else, just as readily as he did Mr. Anderson. No one traveling along that road was safe while young Hicks was there clutching his pistol, and in his timidity and causeless fear, imagining every shadow an enemy.”

Gun Control

Of course, the use of deadly weapons became a hot topic, even 150 years ago. The Luzerne Union ran a storyline titled, “Sad Result from a Bad Practice.”

October 27, 1875

The article went on to say, “This sad event is the result of carrying deadly weapons about the person. This young man, like many others, had been in the habit of carrying a loaded pistol in his pocket, and in a cowardly, if not a wicked moment, used it in the dark, resulting in the death of one person, and a long imprisonment, if nothing worse, for the other. Had Hicks been unarmed, as the law and good custom [require], this sad event would not have happened. It is then a warning to others to abandon the evil fashion of carrying deadly weapons. The law against it should be enforced with more rigor. It is a cowardly and dangerous custom. It is at with good other and manly confidence, and should be prevented by the cooperation of parents and officers of the law.”

Confession

When Hicks met with Alderman Leach the day after the shooting, he told him that he would frequently carry cash for the workers’ wages. Hicks was a boyish-looking 120-pound young man. He was aware of another shooting in Scranton recently, and that friends encouraged him to buy and carry a gun to protect himself. He claimed that it was a dark night and that he had seen two men crouching in the bushes. Just then, Anderson appeared and startled him. Thinking he was about to be attacked and robbed, he “let flicker.”

After hearing Hicks’ testimony and that of Anderson the night before, Alderman Leach placed Hicks under arrest and ordered him to the Wilkes-Barre jail. Later the same day, he appeared in front of Judge Handley. The Judge released him after posting $10,000 bail, paid by his father, with the aid of Ira Tripp.

Re-Arrested

A week later, Hicks was again detained by Constable Rink. He was found at his father’s house and brought before Judge Dana, who ordered him to be held at the county prison.

Judge Dana heard arguments from both sides, and he indicted Hicks for murder with a second count of manslaughter.

November 11, 1875

He sent Hicks back to jail with a $15,000 bond. Once again, Major Hicks and Ira Tripp became the bondsmen.

The Trial

Back then, the right to a speedy trial was truly embraced. Arguments were set to begin on December 10, 1875, less than two months from the shooting. It’s not clear if they started on the 10th, but it was reported that Hicks was a no-show on Saturday, December 11.

December 11, 1875

December 13, 1875

Hicks was found, and the trial began on Monday afternoon, December 13th.

December 14, 1875

From the start, the defense argued that the jury was improper. It was determined that one man was not a resident of Pennsylvania. The man lived in New York with his family. They challenged another member of the jury. They claimed that he was a member of the Odd Fellows, the same organization as the victim. The Odd Fellows published condolences in the newspaper days after the shooting. While the juror from NY was dismissed, the Odd Fellow was allowed to stay.

The prosecution’s case was short and to the point. They questioned Doctor Hollister, who reiterated that Archibald described his attacker. Dennis Shallue was also called. He testified that he walked with Hicks from the streetcar. He also shared that the Hicks admitted to shooting Anderson, albeit because he thought he was going to be attacked.

Joseph Church also testified on behalf of the prosecution. He corroborated Shallue’s statement that Hicks admitted to the shooting. He added that Hicks boarded next door to Ira Tripp, and he was on his way home that evening.

Squire Leach testified that Hicks turned himself in the next morning and admitted to the shooting.

Another witness was called to demonstrate that Hicks had purchased the revolver. Mitchell Carroll testified that he had known Hicks for over fourteen years. Carroll had asked Hicks if he knew of anyone interested in buying a revolver. Hicks said that he himself was interested. He paid Carroll a $1 deposit on the seven-shooter and agreed to pay the balance.

Others were called, and they all supported the prosecution’s argument that Hicks was the shooter. There was no doubt that Hicks was responsible for the shooting. The only question was to determine the degree of guilt.

The Defense

It seemed that the defense didn’t have much to go on. Their client shot and killed Anderson. Their challenge was to limit the damage and minimize his sentence. Even with powerful allies on their side, it was a tall task. Their plan? Paint the defendant as human, yet medically skittish and in fear for his life.

Attorney Palmer gave an opening statement to the jury that said they can’t bring the dead to life, but they can make a decision on how to handle the living. He implored the jury to consider motive and intent. Palmer pushed the theory that Hicks was in fear for his life, and that’s why he pulled the trigger.

They called the doctors who cared for the Hicks family. Dr. Crawford testified that Hicks’ mother was an extremely nervous, timid woman. He claimed that her condition would cause problems when he was treating her. Crawford also painted Edward as a nervous youth. Dr. Hand agreed with Dr. Crawford. This set the stage to paint Hicks as nervous and excitable.

Major James Hicks was called. As Edward’s father, he too claimed that his 20-year-old son has always had a nervous disposition, the same as all of the other children from the same mother. He claimed that Edward was always afraid to go out at night alone.

When Ira Tripp was called, he testified that Edward would frequently carry cash due to his position as weighmaster. Tripp said that Edward came home that evening and told him that he might have shot someone, but he wasn’t sure. Tripp suggested that Edward wait until the next morning to see if anyone was shot, then, if so, turn himself in.

Several other “character witnesses” were called to vouch for young Edward. One man in particular got laughs from the courtroom.

Richard Hutchins, who lived in Wyoming (PA), testified that he’s known Hicks for a few years. He said a couple of weeks before the shooting, Edward told him that he had been jumped in what was suggested to be the same area. Edwards said he was on his way to Sunday school when three men threw stones at him.

When cross-examined, Hutchins testified that he told Edward to be careful because it was a “hard hole.” When pressed on how he knew it was a hard hole, he said he learned it from his aunt, who lived in Providence. The prosecutor then asked, “What hole did she mean? Richard said the whole of Scranton and the courtroom burst into laughter.

With that, the defense rested its case. They called upon the jury to ignore any thoughts of 1st degree murder as the evidence doesn’t support it. They said if the jury believed there was evidence that Edward could have been in fear of great bodily danger, they should acquit him. They asked them to consider that if they believed Edward to be nervous or timid, they should consider that those attributes put him in a state of fear. And finally, if they believed that the evidence showed that he had been jumped before in the same area, that too could contribute to his fear.

Prosecution Closing Argument

Attorney Hubbard Payne presented the closing argument for the Commonwealth. He reviewed the facts of the case, then offered an olive branch to the jury. He said that it was his duty to do what was right for the commonwealth, but also for the defendant. He was quoted as saying, “We cannot, as men, responsible to God for our own acts, ask for a verdict of the first degree.” He continued, “If you find this case lacks the hardness of heart, or recklessness of consequences, it may even be reduced to one of manslaughter.”

September 30, 1911

He added that the jury owed a debt of safety to the community. “You need only be in the court as jurors one week to know what a county we live in. Our boys, as soon as they are big enough to wear breeches, have a revolver stuck in their pocket, the first thing.”

Defense Closing Argument

General William H McCartney, a highly decorated Civil War veteran and lawyer, provided the closing arguments on behalf of Hicks. Oddly, he made it clear that he was employed by “the highest and best people that this county could afford.” He added that it was not the job of the defendant to prove his innocence, but it was the job of the prosecution to prove his guilt.

Source: find-a-grave.com

McCartney painted Edward as “a boy who drank in with his mother’s blood, his mother’s infirmity; a timid, inoffensive boy.” He told the jury that Edward had been frequently carrying money, and he was responsible for docking men of their pay, something that might cause enemies. He asked the jurors, “Was he not sober, of good character? Was he not on his way home?” The General pointed out that there had been no previous trouble between the two men.

The Times Leader said McCartney stated that “the mere fact of killing does not necessitate the inference of malice; that although they (the defense) did not pretend that he was insane, the boy was in an excitable, nervous condition; and that it was their (the jury’s) duty to take him as God made him; for this instance, fear got the better of his reason.”

Political Infighting

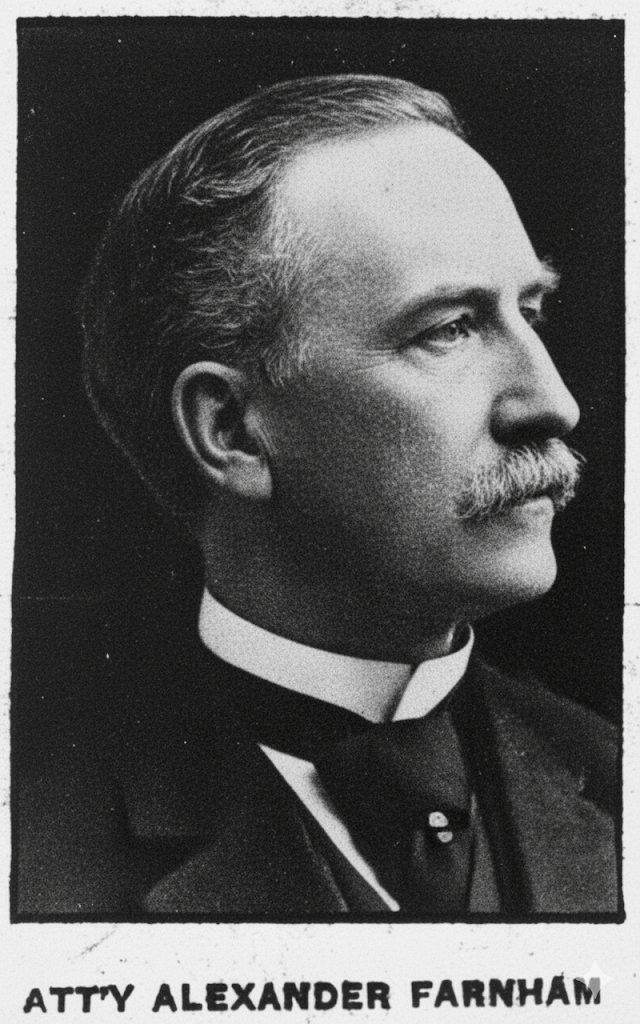

As a side note, there was a lot of political infighting that took place in front of the jury. The District Attorney was Republican Alexander Farnham. He took over the spot from a Democrat in the October 1873 election.

February 10, 1920

Farnham did not try the case because he was reported to be ill. The defense used this to make a case that Farnham was either too lazy or too ignorant to deal with this case. The Defense asked if the voters of the county thought Farnham would get so sick or become so weakened so quickly. During General McCartney’s closing statements, he made it sound like the prosecutors were influenced by Anderson’s wealth. Ah. Politics.

The Verdict

Before handing the case over to the jury, Judge Harding outlined the differences between degrees of murder and explained voluntary manslaughter. With that, the jury was sent to deliberate.

After about 30 minutes, it was clear it was going to take longer than anticipated. They shut down the court and sequestered the jury overnight.

The next morning, on Wednesday, December 15, 1875, after approximately 90 minutes of debate, the jury rendered a decision.

Guilty of voluntary manslaughter. He would be sentenced on Saturday.

December 15, 1897

Sentencing

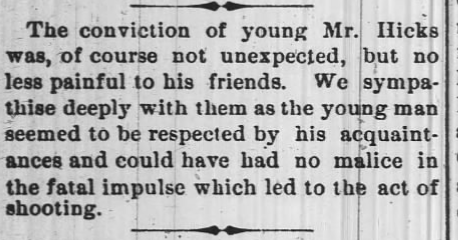

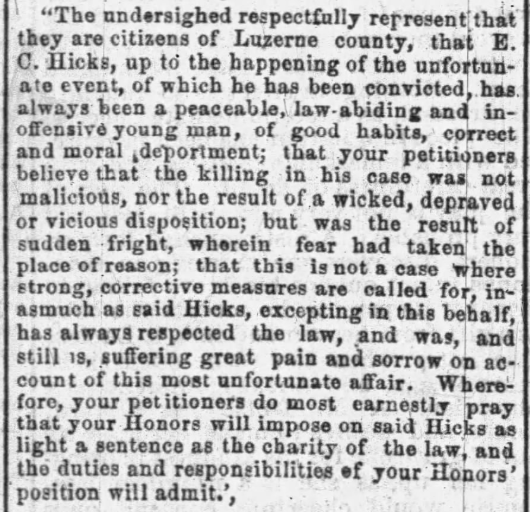

On Saturday morning, December 18, 1875, General McCartney asked to read some petitions for leniency. Of course, given the Hicks connections in the area, petitions were read from some of the most prominent citizens of Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Kingston, and the surrounding area. The list even included many religious leaders in the area.

The Times Leader later published a petition signed by the supporters.

December 28, 1875

Attorney Palmer was next to support his client. The Times Leader said he made “a pathetic and earnest appeal for his client. Tears were shed by members of the Bar.”

Judge Harding was apparently moved by the support for young Edward. He felt bad for the young man, given the circumstances and the number of influential people who supported him. He said that the court would look at him with “an eye of mercy.”

The Judge then handed down the sentence. Pay a $50 fine, plus court costs, and be imprisoned in the Luzerne County jail for thirteen months.

Edward was then transported to the relatively new Luzerne County prison, built in 1870.

1891

Photo: Luzerne County Historical Society

Backlash

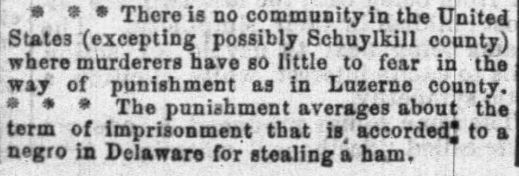

The lenient sentence was immediately questioned. Some newspapers claimed that, while they were not present in the courtroom to hear the testimony, they could only wonder whether the petitions and support from the wealthy members of the community swayed the judge’s decision.

The Times Leader called out one signer of the petition in particular. Scranton’s Morning Republic Editor Joseph A Scranton supported leniency for Hicks, then printed this scathing accusation the day after the sentencing. In questioning the county’s easy-on-crime tendencies, he wrote, “There’s no community in the United States (excepting possibly Schuylkill County) where murderers have so little to fear in the way of punishment as in Luzerne County.” He added, “The punishment averages about the term of imprisonment that is accorded to a negro in Delaware for stealing a ham.” Ouch!

December 28, 1875

Scranton would go on to become a member of the US Congress in 1881. Shocking.

Outcome

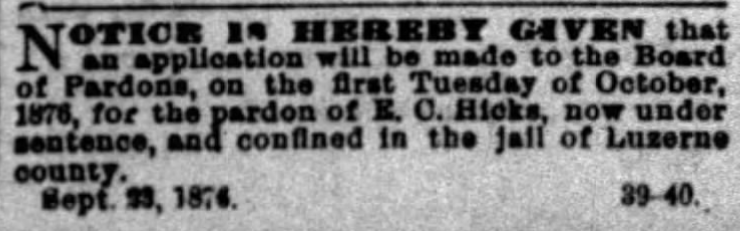

Attorneys for Edward would file a petition for pardon in September 1876.

September 27, 1876

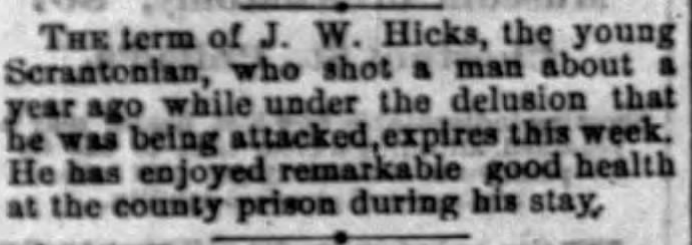

The appeal was denied, but Edward was nearing the end of his term in November and had “enjoyed remarkable good health” during his time in prison.

November 27, 1876

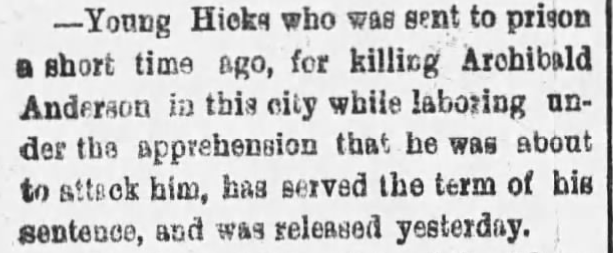

Finally, on December 13, 1876, almost one year later, plus time served, Edward was released.

December 19, 1876

Post Prison

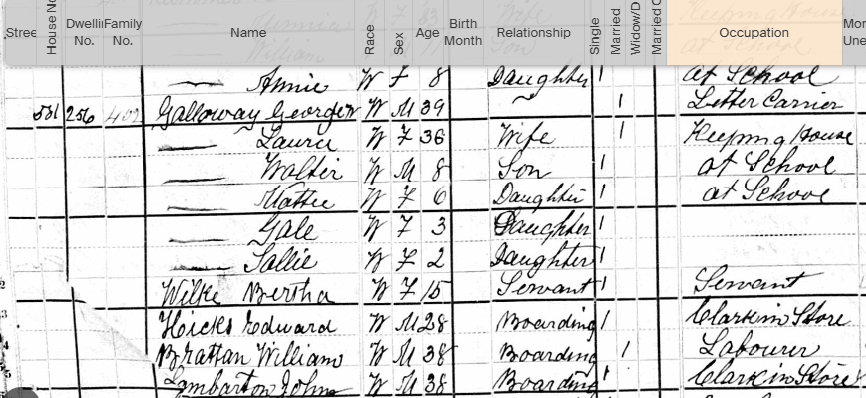

Less than two years after his release from prison, in about 1878, Edward moved to Chicago. He worked at the Clark & Brothers store. There’s no way to determine why he moved, but maybe he wanted to start over and put the pain of killing a man behind him. Or, perhaps he just wanted to join his brother, who was already living there. No one knows for sure.

Boarding at 581 W Erie Street, Chicago, IL

While in Chicago, it was said that he picked up drinking alcohol as a way to deal with the stress of his job. He also started taking laudanum, a form of opium and pain reliever, to help him sleep. This was a common practice at the time, but it was also a drug that would lead to overdose and death.

After years in Chicago, Edward returned home to Pennsylvania to visit his father in Wyoming in the fall of 1884. The family was living at 270 Wyoming Ave, the main thoroughfare through the village. It was clear to James that his son wasn’t well. He convinced Edward to stay home and not return to Chicago until at least the Spring of 1885.

In April 1885, Edward considered moving to Philadelphia, where Clark & Brothers had another store. Again, James, still worried about his son’s health, encouraged his son to delay his move.

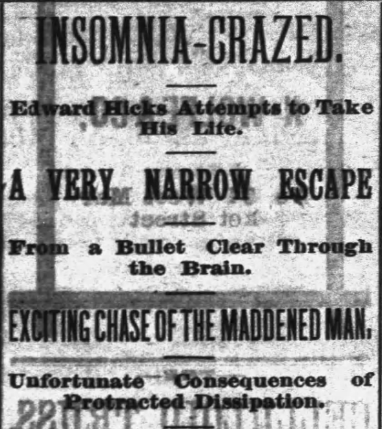

Edward Snaps

Then, on Sunday, May 3, 1885, Edward became irate. It was reported that he went to his room and locked himself in. He didn’t respond to anyone. Finally, the next day, he left home without a word and went into town, but no one knew why or where he went.

When he came back home, James tried to talk to him again. The concerned father attempted to get him to eat and drink something. It had been over 24 hours since his last meal. When James asked if Edward was ready to go to Philadelphia now, Edward replied, “I will fix this thing now.”

Edward grabbed a revolver from the drawer, pointed it at his head, and pulled the trigger. He collapsed to the floor in front of his father. James ran to his son, thinking he was dead. When he was standing over him, Edward grabbed the revolver, sprang to his feet, and ran out the door of their home.

The bullet had glanced off his head and struck the wall. Edward’s ear was burned from the flash, but he was otherwise unharmed.

May 5, 1885

James summoned his neighbors for help. They joined in the frantic chase for Edward. At first, Edward was running toward the Susquehanna River. Before he could reach it, neighbors cut him off. He turned and ran for the mountains on the western side of the river.

He was eventually caught about a mile away from home. He struggled with his captors, but, despite reports, he made no attempt to use the revolver on his father or anyone else.

May 9, 1885

He was taken back home and given some opiates to calm him. He finally settled down around midnight.

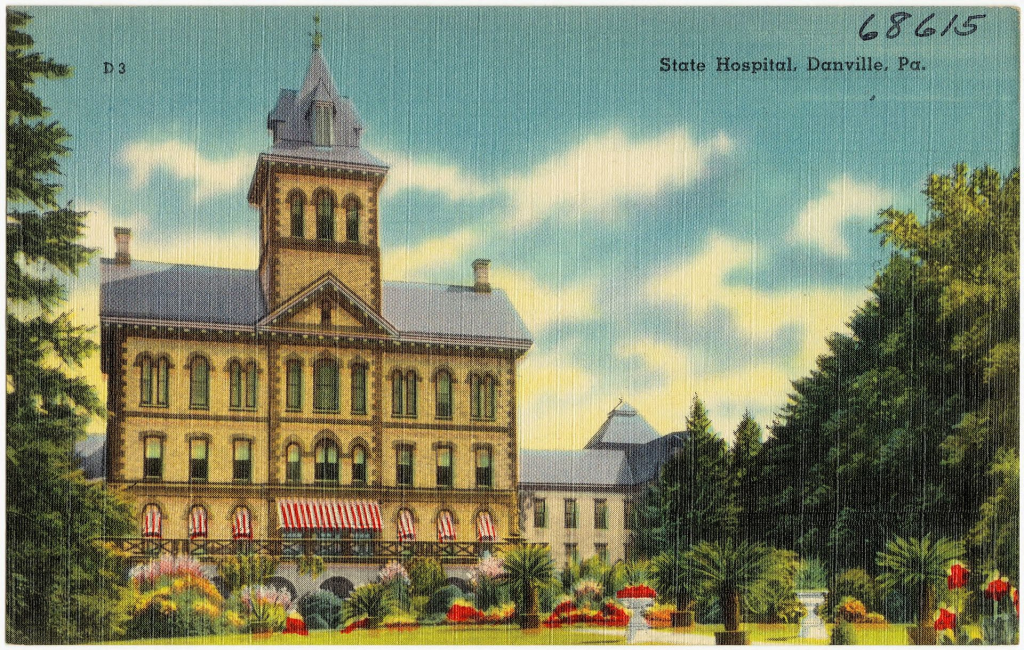

In the morning, Edward was taken to the State Hospital for the Insane at Danville, aka, the Danville Asylum.

May 7, 1885

The facility opened in November 1872, and by the following year, it already had 138 men and 72 women as resident patients.

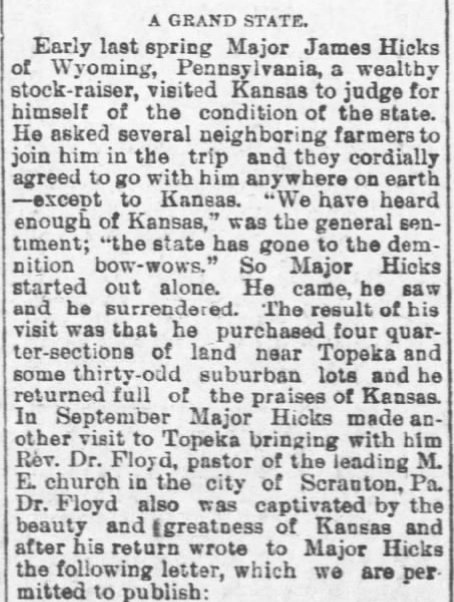

Major Hicks Visits Kansas

In 1891, the Major visited Topeka, Kansas, and ended up purchasing farm land during his visit.

December 13, 1891

Back to Society

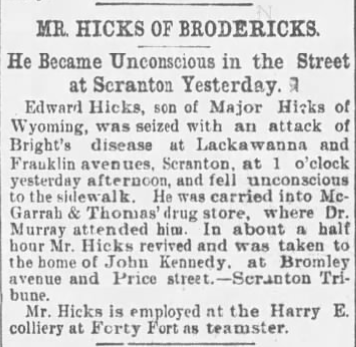

It’s not clear when Edward was released from the Danville Asylum, but by 1894, he was living in Brodericks (now Swoyersville). He was working at the Harry E. Colliery in Forty Fort.

On Thursday, August 2, 1894, he was 39 and visiting Scranton when he collapsed at the corner of Lackawanna and Franklin. He was brought to a nearby druggist for treatment for Bright’s disease, known today as kidney disease. After treatment, he went to the home of John Kennedy at the corner of Bromley and Price Street. John was likely a relative of Edward’s stepmother, Mary Kennedy.

The End of the Hicks Family Line

Over the years, Major James Hicks’ family line would fade away. Of the Major’s eight children, only one would marry and give birth to a child, resulting in the Major’s only granddaughter.

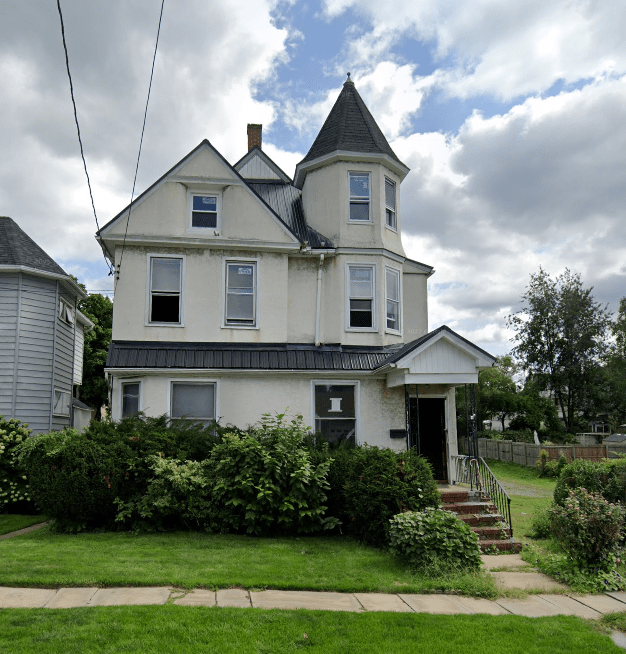

It started with Edward’s brother, James H. Hicks. He died on July 2, 1899, at the age of 46. His obituary included details of his professional career as an engineer as well as his travels to the Western United States. At the time of his death, James was single and living with his sister, Sarah (Sadie) Benjamin, at 2512 N Main Avenue in Scranton.

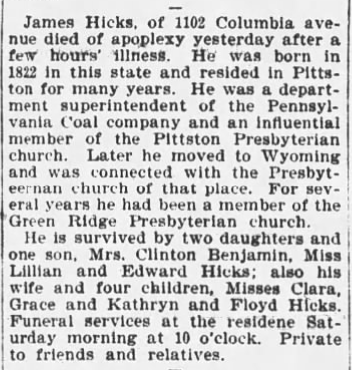

Just three years later, Edward’s father, Major James Hicks, passed away in Scranton on February 19, 1902. He was 79. His obituary highlighted his involvement with the Presbyterian Churches in Pittston, Wyoming, and Green Ridge. He left behind his second wife, Mary, and seven of his eight children.

Just before his death, during the 1900 census, James, Mary, and their two daughters, Grace and Katherine, lived at 1524 Monsey Ave. I believe the Hicks family was the original owners of the home.

At the time of his death, just two years later, the family lived at 1120 Columbia St in the Green Ridge section of Scranton.

James is buried in the Hicks plot in the Dunmore Cemetery.

Next was Edward’s sister. Lillian Hicks, a principal at Central School in Peckville, died on February 14, 1904, at just 44 years old. Like her brother James, she also died at the home of her sister and brother-in-law in North Scranton.

February 15, 1904

She was a well-respected teacher who had been recently promoted to principal of the school.

February 16, 1904

On the morning of July 6, 1905, Edward was at the Dallas Fairgrounds when he experienced “acute stomach trouble.” He was taken to his home in Wyoming to rest. At 4:30 in the afternoon, Edward Carroll Hicks passed away on July 6, 1905, at the age of 50.

July 10, 1905

A decade later, Edwin’s stepmother, Mary Kennedy Hicks, died in Scranton on September 3, 1915. She left behind three daughters and one son. As well as her lone-surviving stepdaughter, Sadie Benjamin, and Sadie’s husband, Clinton Benjamin.

September 4, 1915

She’s buried in the same plot as James in the Dunmore Cemetery.

Mary’s biological daughters with James, Clara, Grace, and Katherine, were all teachers. All were single, and all died in California. Clara died in 1944 in La Jolla. Grace died in 1939 in Los Angeles. And Katherine died in 1956 in Ventura. Grace and Katherine’s bodies were brought back to Scranton, and they were buried with their parents in the Dunmore Cemetery.

The lone surviving son was Floyd. I could not find any information on him, other than his burial record from 1942 in Dunmore.

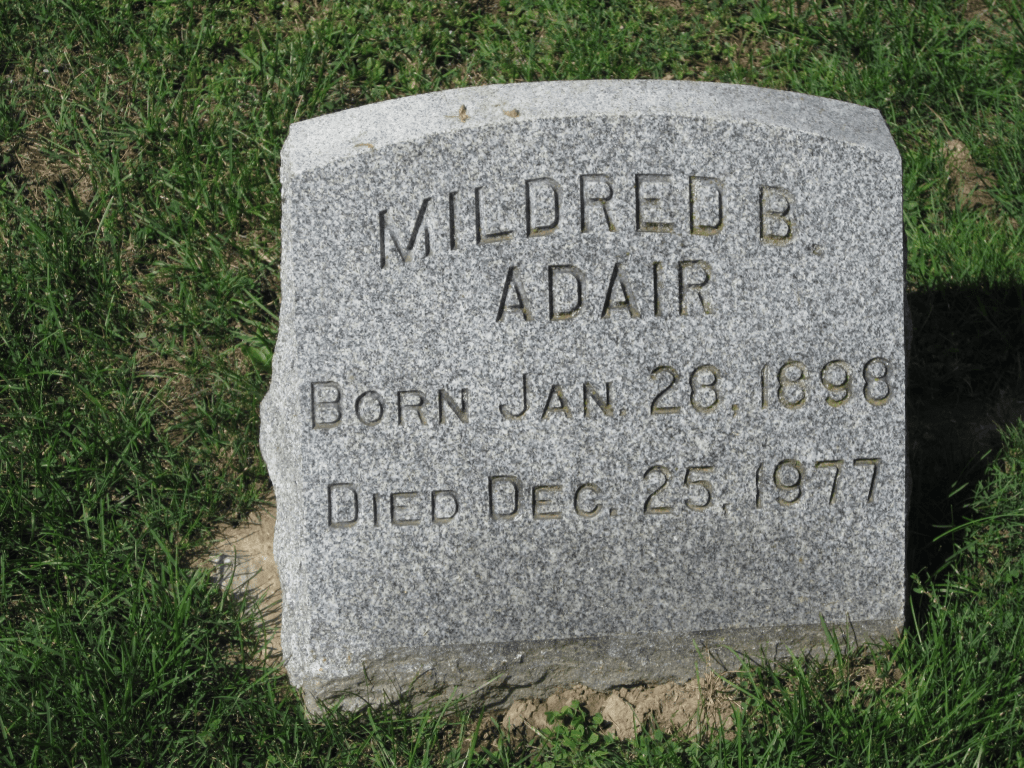

The only child of Major James Hicks to have children was Sarah (Sadie) Hicks. She and her husband, Clinton Benjamin, had one child, Mildred Benjamin. Mildred married J.R. Bennett Adair, a civil engineer, in 1923 in Scranton.

Some time after Clinton died in 1920, it appears that Sadie had moved to New Jersey to live with her daughter, Mildred, and her husband.

By 1950, the Adairs had moved to Garden City, New York. Sadie moved with them again. Sadie died in October 1950 at home.

Mildred and J.R. Bennett didn’t have any children. J.R. died in 1972 in Garden City. After that, it looks like Mildred moved to Hart in western Michigan to be with J.R.’s family. She died there on Christmas Day, 1977.

Legacy

While my research didn’t uncover any remaining descendants of Major James Hicks or Archibald Anderson, I may have overlooked someone. And I hope I did. When I discover stories like these, it’s sad. Two families that were so well-educated, wealthy, and respected just literally faded away. No one is left to remember the accomplishments of Major Hicks, Archibald Anderson, or their families. The same goes for the tragic story of Edward and his challenges.

And while most of the Hicks family could be considered successful, you have to wonder if the murder of Archibald Anderson affected young Edward’s career path and life choices.

Archibald Anderson, Major James Hick, and the Hicks children all had stories to tell. I’m happy to share them on their behalf. Will your story carry on for generations? Or will it fade away, only to be remembered by some random person who discovers it one hundred and fifty years later?

Leave a comment