In the early morning hours of Saturday, September 21, 1872, a man was found dead, lying in a pool of blood near what was then known as Fellows’ Corners in Hyde Park, an area distinct from the current-day Fellows’ Park.

The location was described as being near “Sixth Street in the Fifth Ward.” Reports stated that two men “were passing up the road leading to Hampton Mines,” when they discovered the body “on the brow of a hill, about one hundred feet from where the road turns off from the main thoroughfare.”

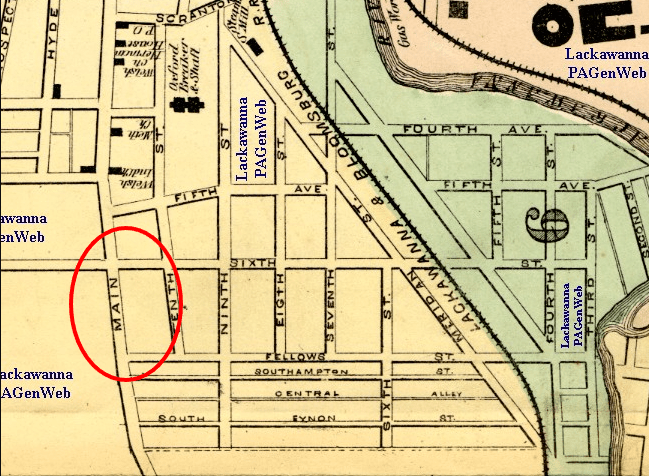

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact location of the murder due to changing street names over the years, but a few clues help to hone in on the location.

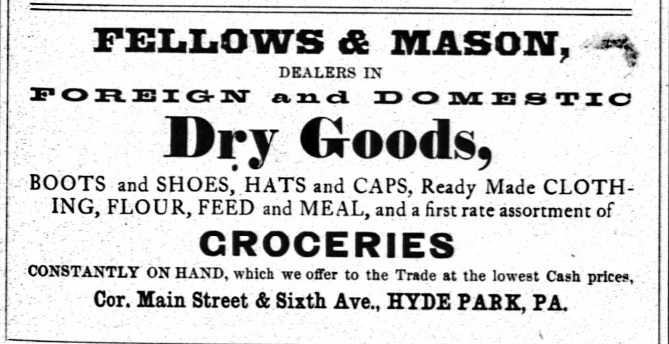

Joseph T Fellows ran a grocery and dry goods store at the corner of what is now Luzerne Street and Main Avenue. This was likely the first “Fellows’ Corners” in Hyde Park.

A snapshot of a map from 1873 is below. It indicates that Luzerne Street was then known as Sixth Street. You can also see Fellows Street on the map. And today, Fellows’ Park sits at the corner of Main Avenue and Fellows Street.

Based on these details, it seems likely that the man was found near the corner of present-day Main Avenue and Luzerne Street.

Discovery

Two men, Messrs. Blatchford and Stevens, were walking through the area at around six o’clock in the morning. When they reached a small blacksmith shop on the crest of a hill, they made their gruesome discovery.

The man appeared to have been beaten to death. Next to the body, they found two large rocks, thought to be the murder weapons.

Identity of the Victim

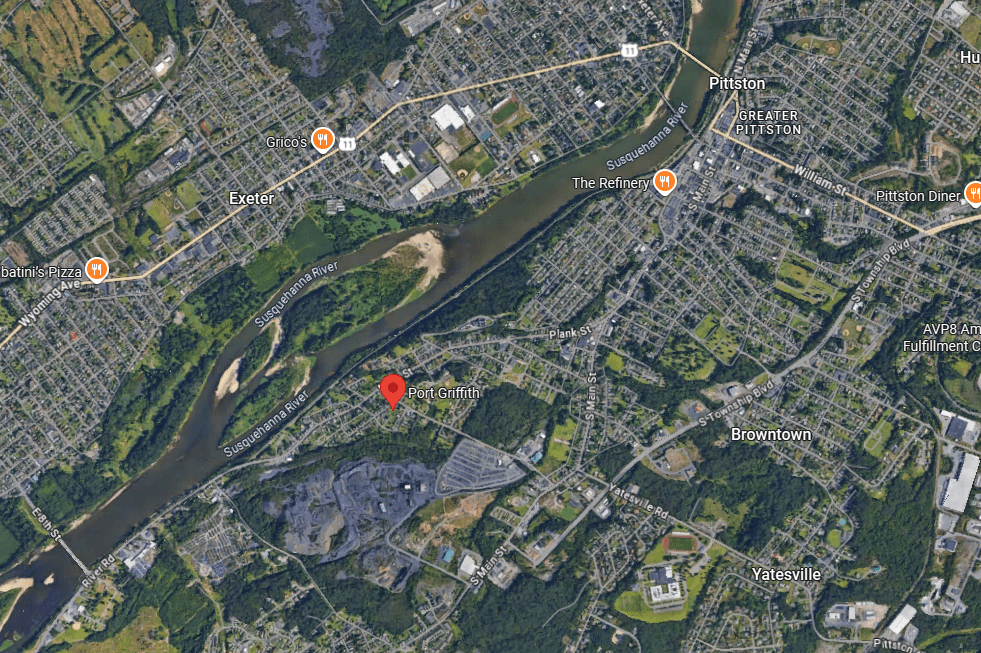

Word spread quickly throughout Hyde Park, and many rushed to the scene to see if they knew the victim. Soon, the man was identified as James Monaghan. He was a carpenter from Port Griffith, a small village along the Susquehanna River near Pittston, Pennsylvania.

Investigators learned that Monaghan had also worked as a bartender for quite some time, but it was reported that he had recently left that job to work his trade in Hyde Park.

The deceased was about thirty-five years old and left behind a wife and two young children who lived in Port Griffith.

Scranton’s Early Period

Scranton was incorporated just six years earlier, in 1866. It was growing rapidly, but it was still a part of Luzerne County. It wasn’t until 1878 that Lackawanna County was established, largely due to the rising population and increasing influence of Scranton.

During the 1860 census, the population of Scranton was just over 9,000 inhabitants. By 1870, it had ballooned to over 35,000, and the city had become “The Anthracite Capital of the World” due to its coal production.

Scranton quickly became an immigrant destination for those fleeing poverty and seeking new opportunities, and it became the fastest-growing city in the state of Pennsylvania.

Those early days of the blue-collar city saw thousands of Irish, Welsh, and German immigrants settle in the area.

Unfortunately, at the same time, it was quickly gaining a reputation for violence. Reports indicated that six murders occurred over the previous six years (1866-1872), and the killing of James Monaghan was described by the Scranton Republican as “for fiendishness, brutality, and utter wantonness, excels all others.”

September 26, 1872

Molly Maguires

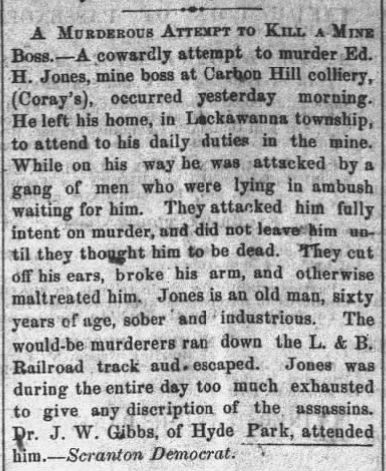

In those early years, the Molly Maguires also organized in Scranton. The notorious gang of Irishmen was known for protecting the Irish mine workers. The shadow organization would retaliate against abusive mine bosses, protecting their brethren from poor working conditions. They would also seek revenge when they felt the system failed their colleagues.

Just weeks before the Monaghan murder, members of the gang attacked Ed H. Jones, a local mine boss. They cut off his ears, broke his arm, and left him for dead.

August 14, 1872

Then, on the same day that the news broke of Monaghan’s death, reports of a shooting in Spring Brook hit the papers. It was reported that men, allegedly belonging to the Molly Maguires, waited for a man at the Lackawanna Train Station. When the unsuspecting man exited the train, the men asked him to join the organization or face the punishment that Ed Jones received.

September 25, 1872

The man refused and warned them that it would get violent if they approached him. The gangmen attempted to grab him when he pulled a revolver and fired at his assailants, striking one of the attackers. The men return fire, but the man escaped. The injured man was taken into custody, but no further information was available.

In yet another instance from November 13, 1872, just months after the Monaghan murder, the Mollys left a threatening note for another carpenter, this time in Wilkes-Barre. They forced him to leave the area under threat of death.

According to the Luzerne Union, the note contained “numerous coffins, skulls, and cross bones, and other cheerful pictures.”

November 13, 1872

Coroner’s Inquest

Alderman John Levi, who also ran a grocery store near Main and Eynon Street, called a panel of jurists to review the details of the case.

During the inquest, Dr. John Gibbs testified that he was returning to his home at 30 South Main Avenue after a house call to Bellevue. He said he passed Fellows’ Corners about two o’clock in the morning. He said he saw two men standing by a small tree, across the street from where Monaghan was later found. When he passed, he said he had heard one man say to the other, “There he goes!”

At the time, he thought the men were waiting to attack him. He replied, “Yes, here I am, and my name is Dr. Gibbs.” He said the men took a couple of steps towards him, but he didn’t recognize either man. Even with the moon shining brightly that night, all he could see was that one was tall and wore a hat, the other was small and had on a cap.

Monaghan’s friend, William Hennessy, testified that the two men had come to Hyde Park from Scranton, arriving on the seven o’clock car on Friday evening. The two had parted ways in front of J. W. Hoban’s saloon at Price and Main. At the time, Price Street was Franklin Street. He testified that he didn’t believe that Monaghan was drunk when he last saw him.

Hoban testified that Monaghan had been in his saloon, but had left by himself at about 9:30 pm. He also said that Monaghan wasn’t drunk and seemed to be “a very quiet and inoffensive man.”

Mrs. Martha Thomas, who lived nearby on Main Avenue, stated that between two and three o’clock, she heard gunshots and a couple of people walking down the sidewalk. She said she got up and looked out of the window, but couldn’t see anyone. She went back to bed. Just after three o’clock, she awoke again. This time, she heard people running outside. She woke her husband, Thomas, to say something was wrong, but he shrugged it off as routine noise in the area. He claimed that every night he would hear gunshots.

The coroner, Dr. William Heath, also testified. He said he was called to undertaker Joseph Becker’s cabinet shop to see the victim. The doctor said Monaghan’s body was cold and stiff. He said the blood from his head was clotted, as if he had been struck with a stone or club in the back of his head. He said the stone cut through the skull and that the man had been struck twice while he was on the ground. The injuries were to the right side of his head, cutting through the right ear. He had a fractured jaw and broken skull. The doctor claimed the injuries to the head would have caused immediate death.

The inquest continued the following day, and on October 3, 1872, it was surmised that James Monaghan had been murdered.

October 2, 1872

Unsolved Mystery

Unfortunately, there is no additional information on the outcome of the case. It seems that whoever murdered James Monaghan literally got away with murder. His wife was left to raise their family.

Violence became more prevalent in the city. A few more instances were reported within months of Monaghan’s death. It’s difficult to determine if the cases were related or due to the population increase.

Additional Violence

Just two months later, on November 16, 1872, Constable Thomas McNamara was found dead on Main Avenue in Taylor. He appeared to have been beaten and slashed with a knife. To the best of my knowledge, the killer was never found.

November 20, 1872

Then, just days later, on November 24, 1872, John Garrity was found dead across the street from his home along Leggett’s Creek near “the notch.” Like many other assaults during that time, his skull was bashed in by a rock that was found nearby.

November 25, 1872

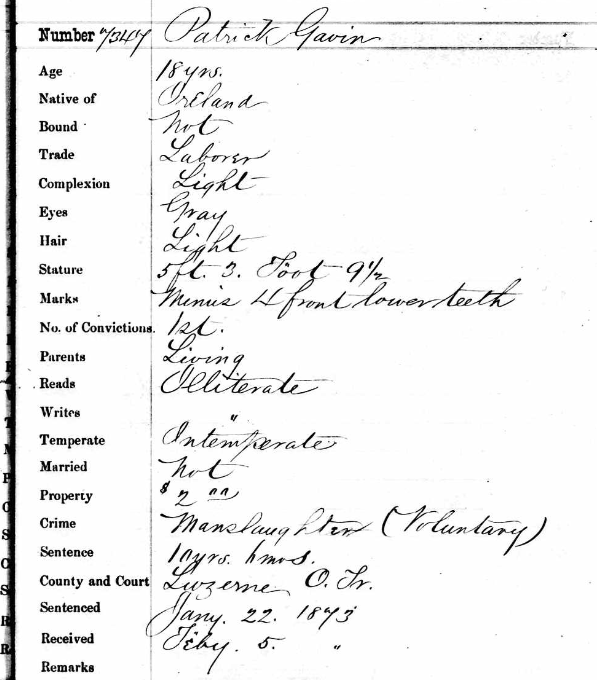

The investigation revealed that he and his friend, Patrick Gavin, spent the night drinking and later got into a fight. Gavin, who lived in the Notch with his sister, Mrs. John Jennings, was arrested and eventually tried for the crime. He testified that he became enraged after drinking “bad whiskey” and didn’t recall how or why he committed the crime. He was sentenced to a $500 fine and 10-1/2 years in Eastern State Penitentiary.

Intake Record

Crime Report

Starting in 1870, the county produced a Prison Commissioners’ report that was published annually. The purpose was to break down the statistics for the prisoners. Often, crime reports during this period tended to include ethnicities.

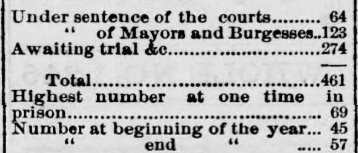

The 1874 report showed that throughout 1873, 461 people had been committed to the Luzerne County Prison.

February 26, 1874

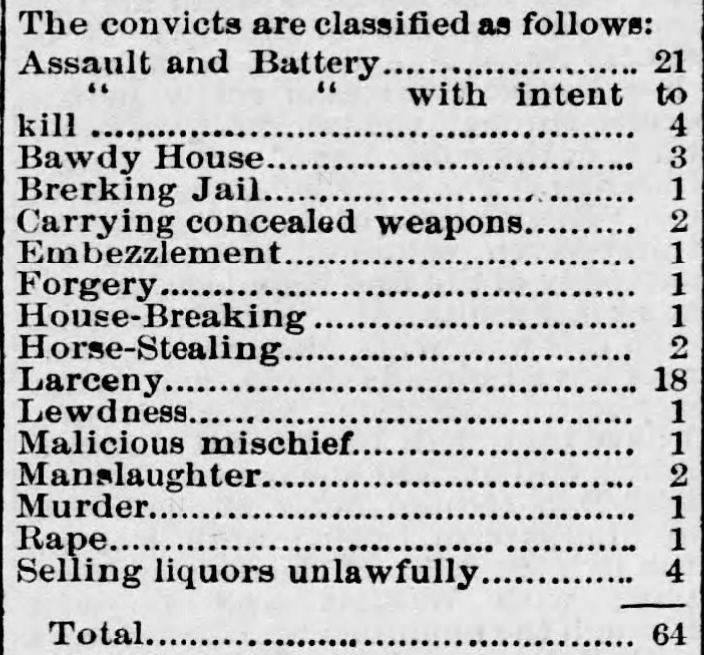

At that time, there were only 64 people actually in prison in the county. The majority for Assault and Battery, with Larceny a close second.

The same was true for those awaiting trial. Assault and Battery (56) with Intent to Kill (15) led the crimes, with Larceny (47) a close second.

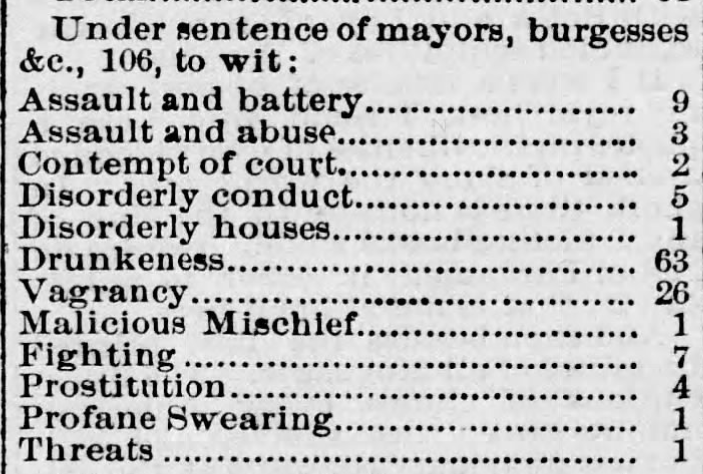

Those who were sentenced by the mayor or burgess were largely due to drunkenness and vagrancy.

February 26, 1874

Clearly, drinking and fighting were two of the main causes of disruption in the hard-working town.

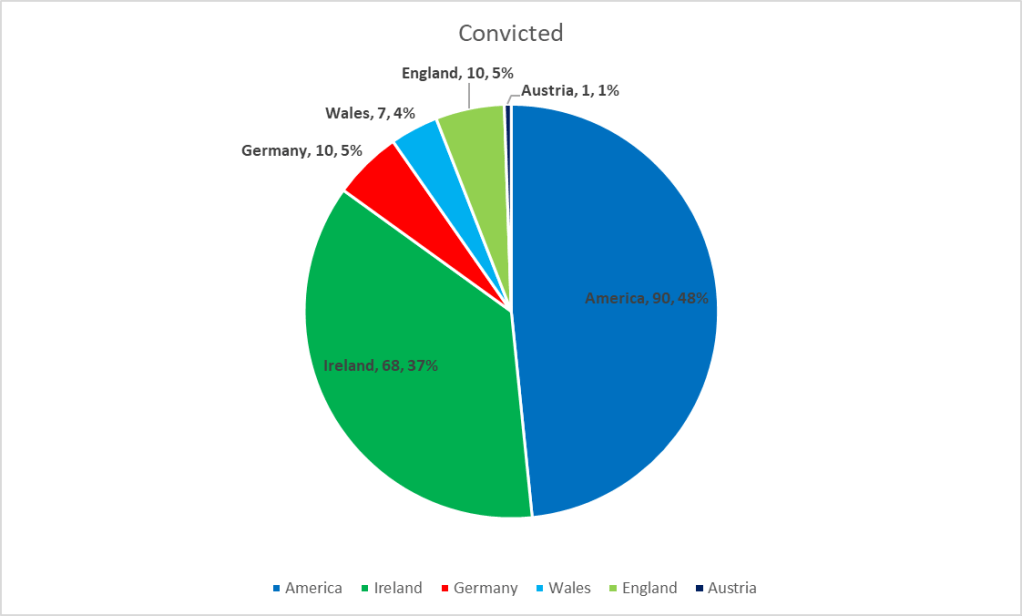

Of those convicted throughout the year, the majority were considered American, but the Irish were a close second.

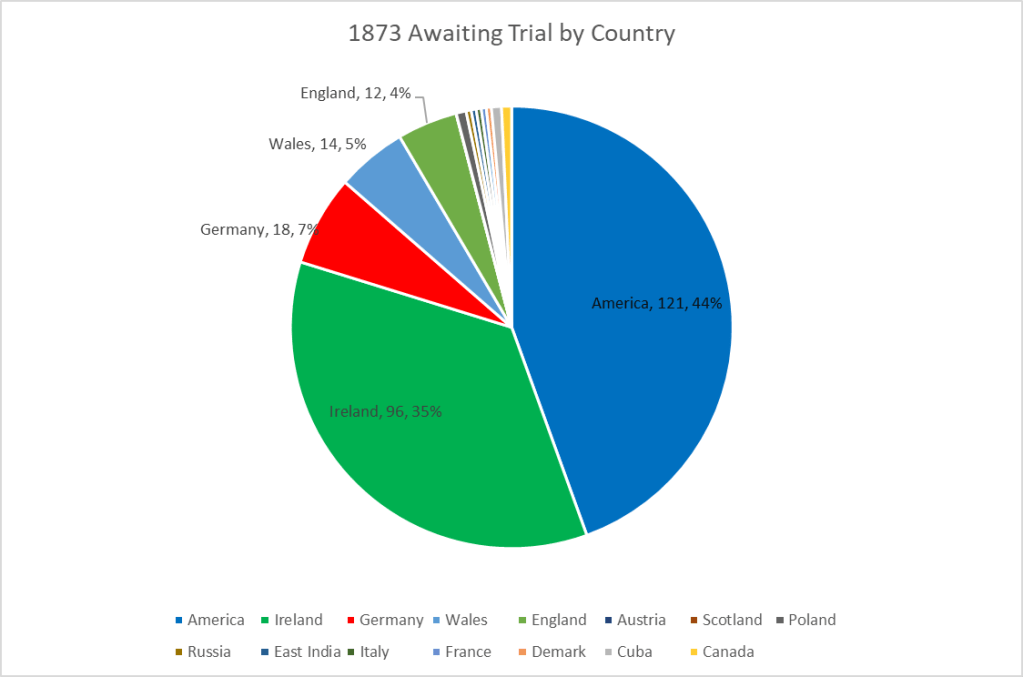

For those awaiting trial, it was definitely a more diverse crowd. Still, Americans led, but the Irish were next to the early settlers.

Conclusion

No one knows what happened in the James Monaghan case. But what is clear is that the working men of Scranton had a penchant for drinking and fighting. Was his death the result of a bar fight? Did his friend William Hennessey have any involvement in his death? What about the two men who said something to Dr. Gibbs? Were they lying in wait for Monaghan?

What happened in Constable McNamara’s case? Was it a drunken brawl? Was someone out for revenge? Were these two cases related?

And finally, did the Molly Maguires have any involvement with either of these unsolved cases? While their targets were mostly mine bosses, it was reported that they threatened another carpenter in Wilkes-Barre. Was it a coincidence that Monaghan was a carpenter?

We will likely never know. One thing is for sure: James Monaghan died a brutal death and left his grieving wife and family without their husband and father.

Leave a comment